| 312 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

ed in the battle, also flowers were placed on the graves of relatives.

Afoot in a Blizzard.

It was a warm day in February when I left Peacock's ranch in the afternoon to go to Stuart, Nebraska, sixteen miles and across an open country. I had not gone far when a blinding blizzard overtook me. I could not turn back and face the storm so held my direction by the wind. I knew that I would hit the North Western Railway and hoped to follow it to Stuart. Finally, I came to Mr. Carberry's home, a mile out of Stuart, scratching the sleeted snow off of a window, I saw the family sitting comfortably by the fire. I thought to knock at the door for admittance, but did not although wet to the skin and it was night. I said to myself, "What if this was the end of life, footsore and worn, I was standing at heaven's gate and knocking and I was not admitted?"

I followed the track and reached the village, but did not have one cent of money and had missed the train for Neligh, so went to a little inn kept by a minister and his wife, whom I had often befriended and stopped with them for the night. I did without supper, but had a bed and breakfast and when I asked them what my bill was they replied fifty cents, I thought for the moment I could not pay it, but fortunately for me an Indian doctor was stopping with them, too. Knowing an Indian's love of colors I showed him some beautiful Sunday school cards. He bought fifty cents worth which aided me in paying my bill.

Christening a Frontier Baby.

Once I received a letter from a young husband that lived thirty‑five miles north of Ainsworth, Nebraska, urgently requesting that I would come to his place and christen his newly born baby boy and mentioning that his wife was a Lutheran. I went by train from Neligh to Ainsworth 110 miles, then on foot from Ainsworth to his home

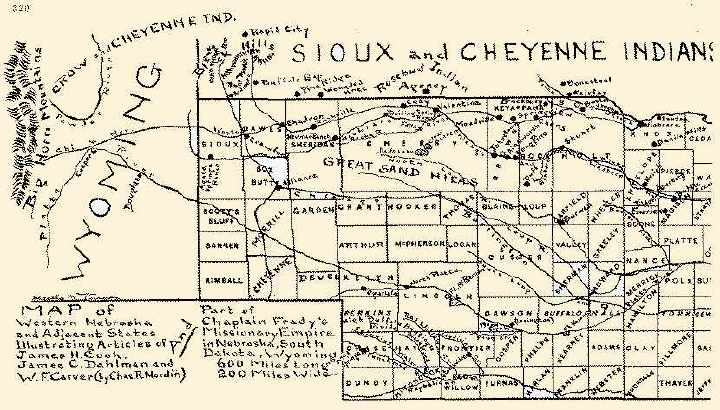

Missionaries like Chaplain Frady as well as editors, were given annual free passes over the Chicago and Northwestern Railway during the pioneer period. This fact will help explain why Chaplain Frady could make long journeys with very little money in his pocket.

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

311 |

where I baptized the baby and wrote its name in a Bible. Next day returned as I had gone, making 220 miles by railroad and 70 miles on foot. I had to bear my own expenses as the man was poor and unable to meet any of the expense. A week later, I received another letter from the same husband stating that his wife had died. When I remembered how thankful the mother was and the joy that shown on her face in having her darling babe christened according to her faith, then the effort I had gone to in performing the act for her entered into insignificance.

Driven Out in the Night.

One time after walking nearly all day to reach a new settlement in Keya Paha County, Nebraska, as I approached the home of a man by the name of Long, he came out with his Winchester in hand and demanded, why my presence. I told him my business and he excused himself, saying that the "Pony Boys" had threatened to kill him on sight and that he did not allow any stranger to come near him until he was satisfied that nothing was doing. There were no other families in the vicinity of Mr. Long, but he said that a man had visited him that morning by the name of Heiges, who said that there were some settlers near him. Mr. Heiges had driven across the prairie about five miles and Mr. Long said that I could follow his wagon track through the grass, there being no road. As Mr. Long did not invite me to tarry over night with him and the sun would soon set, I went on at a "high lope" hitting only the high places. It was dark when I reached the Heiges' home. I told them my mission and Mrs. Heiges said in response that she did not believe a word of my story and that for me to travel on. I pleaded my tiredness, my hunger, but she said, "No, go, or I will unloose my bull dog" which was raving and trying to break its chain to get at me. I put my hand back to my hip pocket and said, "Lady just turn that dog loose and I will make a sieve out of its hide." "Oh, don't kill my dog!" she said, and in turn, I told her to leave the dog alone and I would have my ammunition left for some other occasion. Then I asked her if there was any other place near by where I could stay for the night. Pointing in a direction, she said that a man by

| 314 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

the name of Clopton lived three miles away. In answer I said, "How do you expect I can find his house in the dark, with no road and a thousand chances to miss it"? Then I asked her if they had any guns, she said, "You bet, yes we have, a Winchester and double barrel shot gun." Then I said, "Just let me stay over night and I will lie on the floor. You can hold the shotgun and your son can hold the Winchester and if at any time in the night I turn over, wink an eye, or flutter a feather, then turn your firearms loose on me." "We will not keep you under any plea, just travel on" was her reply.

Called Back by a Song.

Seeing that my suggestions were in vain, I started off, but began to sing on the night winds "Jesus Lover of My Soul, Let me to Thy bosom fly". I had only gone a few rods when Mr. Heiges called to me to come back and he told his wife that no person wishing to do them any harm would go off like that singing that song. I was invited into the house and Mrs. Heiges prepared something for me to eat. In our conversation I told him that I was a soldier in the Civil War. He said he was too, and we found out we were both in the same brigade. That settled the matter, bedtime came and I slept by the side of Harry, their son. Next morning Mr. Heiges hitched up his team and we called on all the settlers here and there. The following day we organized a Sunday school for the community. Explanation: Mr. Heiges had built a log house of two rooms. They lived in one room and kept their span of mules in the other, fearing that the team might be stolen by the "Pony Boys". In speaking about the Sunday school thereafter, I called it my "Bull‑Dog‑School".

"Butcher Knife" Sunday School, Keya Paha County.

Another time as I was approaching a settlement on foot, I saw a girl about ten years of age leave her home and come towards me. She ran into a shack between us and quickly out again and running towards her home did

R. H. Clopton was a pioneer in social reforms. I knew him well. He helped organize the prohibition party in that frontier region in 1888. My correspondence with him lasted through many years. He was a noble public spirited man.

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

315 |

not see a cactus bed as she kept her eyes fastened upon me and stepped in the middle of it with her bare feet. The long thorns pierced her feet to the bone and the poor child could not get out. Going to her, I lifted her out and began to pull out the thorns causing the blood to flow freely. We were both under a raise in the ground and could not be seen from her home. When the mother and a young lady, staying with her, heard the child's screams of pain, they became alarmed and came running to us to learn the cause. I saw the mother was hiding something beneath her apron but when she found I was not harming her girl and that all was safe she drew a butcher knife from under her apron and said that she came thus armed to defend her girl. They carried my books, and taking the child in my arms we went to the housee (sic). When I was eating my supper I told the mother if she would send her two boys to the neighbors and tell them to come over we would have a meeting, that evening. The people gladly came out and after a short service we organized a Sunday school. My chief plea was if they would have a Sunday school, that as homestead seekers came that way, a good element would settle thereabouts, also that in the near future a new county would be organized and my opinion was that their community would be near the center of the county, and if they had votes enough they would secure the county seat. Time proved my prophecy to be true and Springview, Keya Paha County, is the town. My name for that Sunday school is "Butcher Knife". I used generally every argument that seemed feasible inducing people to have schools and to note the many queer instances connected with the planting of the 500 Sunday schools would fill a volume.

A Buffalo Gap Oyster Supper.

I had no greater friends in my work that the cow‑boys, sheep herders and miners. A whole hearted welcome was extended to me in any cow‑boy camp reached. Of course I had to help myself, put my team up, feed them and hitch them on when I wished to leave. At meal time, I had only to draw my chair up to the table, but had to wash the dishes I used, and at night roll up in my own blankets. If I needed any money to help me on the way, all that was

| 316 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

necessary was to mention it. If I wanted to go on a "roundup" a saddle pony was furnished me.

At the close of a revival meeting which I held in the Gospel tent at Buffalo Gap, we contracted a debt for the purchase of an organ, chairs, my hotel bill and in all amounting to nearly $500.00. How to meet the debt was considered. I proposed an oyster supper which was agreed upon and advertised. We bought up all the oysters in the new place besides crackers, a barrel of apples, large quantity of candies, sandwiches and other things for the occasion. Ed. Lemon, Superintendent of a large cattle outfit, came to me and said all the cow‑boys in the country wished to come to the supper, but there were not enough respectable women to go around and he wanted me to tell him what to do? I told him that there had been no smelling committee appointed and as it was a public supper for him to tell the boys to be sure and come and have the "time of their life." This news certainly pleased the boys and each came with a partner, feeling that both were as welcome as any other persons there. The gathering was held in a large hall and "help yourself" was the word. No charge was made for anything, but each put into the treasury box the amount they felt to give. We had the organ there that night and the girls rendered splendid music, old time songs were sung, and many voices joined in the choruses. No swearing or unmanly utterance was heard, no complaint of any kind was made and all enjoyed the occasion, which lasted until midnight, at which time it was requested that all would stand and prayer was offered in dismissal. At the close the treasury box was opened and it was found that more money was placed therein than was needed to meet the entire indebtedness, many five and ten dollar bills were counted in the contribution.

Sheep Herders on the Plains,

It was my pleasure many times to visit the sheepherders in their lonely days out in the wilds of the frontier. I always carried choice reading matter, such as good books and magazines, to give them, which were gladly received. At times when my daughter was along with me, she would play the little organ and sing songs for them.

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

317 |

Once when I was in Crawford, Nebraska, I called on the editor of the newspaper of that place. He told me that his son was herding sheep at a certain section in Montana, but he had not heard from him for two years, and that his wife and mother of the boy was grieving herself sick over him, thinking her son might have died or had been killed. On the ranges in many places there was serious trouble between the cattlemen and sheepmen over the grazing country and many herders were killed. The man gave me a description of his son and I told him that I would keep a lookout and try to find him or learn what might have happened to him. One day, passing along on the Crow Reservation, I saw a band of sheep at a distance. Driving up to them, I met the herder and quickly saw he answered the description given me at Crawford. I asked him his name and he said "Red" to which I replied that the name only fitted his red hair. Then I asked him if his name was and if his parents did not live at Crawford, Nebraska? "Yes", he answered, Then, I told him about his mother. He gave me a brief outline of his life, how he was out with the band of sheep three months at a time, then when he was relieved for a week and received his pay, he would go to Billings, Montana, spend his money and return to his herd flat‑broke and half‑drunk, that he was ashamed to let his parents know how profligate he was. I got him to promise to write to his mother and on leaving gave him a testament and a few papers to read.

Many of the sheepherders go crazy being all alone for months and all that time not seeing a person to talk to, beside hearing constantly that monotonous bleating of the sheep. They are to be pitied and encouraged to live a godly life.

Miners.

We handle the gold and silver coins unthoughtful of the privations and hardships endured by the men in mining the precious metal.

Wm. H. Ketcham was one of the pioneer editors at Crawford. He is probably the one referred to by Chaplain Frady. Editor Ketcham was a soldier of the Civil War, an expert printer, a strong partisan republican. He published many newspapers during thirty years of pioneer Nebraska days. A. J. Enbody was another early Crawford editor. I do not recall his family.

| 318 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

In my mission work, I made it a practice to visit as many miners on the field as possible, hoping to do each miner some good, and always held meetings at the mining camps.

Rev. Williams, Superintendent of the Methodist Missions in the Black Hills, was with me when we called at the "Etta Tin Camp" late in the afternoon. I went to a hotel and asked the proprietor what he thought about having a religious meeting in the camp that evening. He said, "You d___ fool, you would not get out of the camp alive if you undertook such a thing". I asked him if he had a monopoly on the camp, if so I had better go on, and if not I would take my chance on the killing proposition. I then called on Professor Gilbert E. Bailey, the Superintendent of the works. In the introduction I found out, that in a way I knew the professor. He had formerly belonged to the faculty of the Nebraska State University at Lincoln. Professors Bailey and Aughey, Chancellor Fairfield and S. R. Thompson, Superintendent of Public Instruction, conferred with me when I was a member of the Nebraska Legislature 1876‑77 concerning the educational laws of the state, also relative to matters pertaining to the University. At that time I was chairman of the Educational Committee. The professor said that he and his wife would be pleased to entertain Rev. Williams and myself, for us to put the team in the barn and tarry with them until the next day. As to holding a meeting, he informed me that the only place where a meeting could convene was in the mess rooms of the camp, and that he would see if the rooms could be had after the supper was over for the camp. The request was granted and I set about to notify the camp. I called at every saloon, gambling place, questionable places, homes and miners' shacks and invited all to attend the service. Professor Bailey sent word to the men in the mines below that they were to come up and needed not to be relieved by the next shift.

When the time came for the meeting, there were about six hundred people present, including three hundred miners, one hundred saloon men and gamblers, one hundred fancy women, together with cooks, laborers, and other persons.

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

319 |

The meeting was opened with a song service. In all my meetings far and near never did I ever hear better singing of the old familiar pieces. In addressing them I took for my text Ecclesiastes 7.29, "Lo. this only have I found that God hath made man upright, but they have sought out many inventions". In thought, I carried those present back to the time when they were innocent children and in prayer at their mother's knee and tucked into bed by loving hands with good night kiss from her sweet lips, how she watched over them as they grew into manhood and womanhood. Finally as she was dying they gathered at her bedside and promised to live true to God and meet her in heaven; but in after life they were cursed by man's inventions, led into sinful lives, casting aside honor, self‑respect and virtue and having no hope of eternal life. I spared not the gambler, the whiskey vender, nor the prostitute, but in the close, in tenderness and a fatherly feeling for them, I showed the mercy of God, "Who was not willing that any should perish, but all should come to repentance". Every questionable woman present came to me after the meeting and said that they would quit their evil lives if I could tell them where to go. I was nonplussed, for I knew no private home anywhere was open to receive such a woman or girl.

Going back to Professor Bailey's home he said, "Elder, do you know that you made a grand mistake at the meeting?" Stating further that over five hundred people had come prepared to give me a dollar apiece if I took up a collection, as it was the first meeting ever held in their camp, but I told him it was not for the dollar I labored, but for the winning of men to God.

Professor Bailey asked to be excused, stating that he had an unfinished draft of a double reverse curve for a track in a bridge then in construction across a gulch for the purpose of running flat‑cars to haul the ore from the mines to the mill. He said he was perplexed in getting the draft complete. Taking his set of mathematical blocks, I placed them in position and he saw at once his miscalculation. He thanked me for my assistance.

That night the Rev. Williams and myself occupied the same bed. I noticed he was restless and he told me that

| 320 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

the gamblers and saloon keepers would surely kill me in the morning for denouncing their business so forcibly, but I said kill or no kill, I was going to have a good night's rest and sleep. In the morning I could see he was still very nervous, so I told him as soon as he had his breakfast to excuse himself, hitch up his team and drive to the top of the gulch one mile or more away and wait for me and I would go up on foot. He accepted the proposition and drove off much relieved in mind. When he was gone, I told the professor what the matter with him was, and he said, "Oh nonsense, he was as safe as any child in the campl" Before bidding the professor and his good wife goodbye, he said if I would come back in the near future that he would have his men cut logs and build a church for me. I told him if I could find a minister who would come with me to take the work that I would surely return at an early date. After leaving his office it took me one and a half hours for me to greet and shake hands with the' saloon men, gamblers, miners and women who wished to say goodbye, and when I reached the head of the gulch Rev. Williams was eagerly waiting for me and was much surprised that I had escaped with my life. Not long afterwards I received word the "Etta Tin Camp" was abandoned.

Railroad Ride With Gunmen.

When the North Western Railway was being constructed from Buffalo Gap to Rapid City persons could ride part way on the construction train. Several parties boarded the train. Most of them rode in the caboose, but there were a dozen or more gamblers, thugs and confidence men who rode out on the flat cars and I went out too and sat down on a keg of spikes. One man came up to me presently and asked me abruptly who I was. In reply I said I did not know that it was any of his business. Then he said, "Your fine clothes tell me that you are either a merchant or some mine owner." Well, I told him, if he knew, why did he ask me. Then he began calling me all kinds of vile names.

Chicago and Northwestern Railway, then called the "Elkhorn" railway completed its line from Chadron to Rapid City, S. D., in the summer of 1886, thereby putting out of business a large army of freighters who had carried on the worlds business with the Black Hills for ten years.

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

321 |

I just laughed at him and told him to return to his companions and tell them how much he had learned. After a little while the train stopped along side of a creek and the trainmen pumped water into the boiler and tank of the engine. I stood looking at the stream when one of the lawless outfit came up behind me with a revolver in hand and struck my shoulder with it at the same time shooting into the water, again he fired and I asked him if he was trying to hit a chunk of wood which was floating in the stream. I reached out my hand and asked him to let me have the gun, which he did and I fired twice at the wood hitting it both times. On handing the gun back to him, I told him he could not hit the door if he was inside of a barn.

The train started on and the whole outfit came to me and one of them said, "See here, pard, we tried to get you mad by calling you bad names, but you only laughed it off; then we tried ot (sic) scare you by shooting by your head, now we want that you drink with us," offering a bottle of whiskey. Then I said to them, "There is a limit to all foolishness, I did not care for your abusive words or your shooting, but your drinking proposition is the limit". I gave them a temperance lecture after that, which I am sure they never forgot. I used them as true objects of how sin had demoralized a man lower than any of God's brute creation. I further told them how they were once boys loved by dear mothers and had the opportunity to make honorable men and be a blessing to humanity, but now they had given themselves over body, mind and spirit into the hands of the devil, bound for ignominious death, and to pass eternity away from God. At the end of my talk to them, I asked them if they would not all bow their heads and I would pray that the Heavenly Father would still show mercy to them so that they would repent and call on him to forgive them.

The

train pulled up to the terminus and everybody got off. The next day

I met a man in Deadwood and he asked me if I was not the person that

those toughs tried to intimidate the day before on the construction

train. When I told him I was, he said that all those in the caboose

looked on and were trembling for my safety, and they all heard

|

© 2004 for the NEGenWeb Project by Ted & Carole Miller |

||