sel to fight these land tax cases. Meanwhile the

United States Supreme court in a similar case in Kansas

had held that the land was not subject to tax for two

reasons: First, because the company had not paid the fees

and received their patents; Second, because if the land

was sold for taxes and the title acquired by a tax

purchaser it might defeat the provision of the land grant

act which provided that under certain conditions the land

should revert back to the public for settlement. The

editor of The Lincoln State journal dared to pronounce

this decision in the United States Supreme Court: "Sheer

nonsense which would defeat any tax ever being collected

on the land." Many of the counties had issued bonds and

warrants based on calculations including the taxes on

these lands. They now found themselves unable to meet

their obligations and their paper greatly depreciated.

The revenue system of

the state was a failure. The Omaha Herald of August 22,

1873, declared that for four years one-third of all the

property owners in the state had refused to pay taxes.

More than half the Otoe county real estate was delinquent

for taxes prior to 1873. Single individuals owed from

$2,000 to $3,000 for taxes. The county and municipal

bonds which had been so lavishly voted to aid railroad

and other schemes were now an intolerable burden.

When the legislature

met in 1873 Governor Furnas told them that there were

$300,000 taxes delinquent and more than that of local

taxes, that there was great stringency in money and a

meagre price for farm products. The legislature was

advised to authorize a constitutional convention. There

were two factions in the Legislature. One of them wanted

to comply with the constitution then in force which

provided a plan for making a new constitution,--requiring

two years time. The other faction from the western

counties of the state were determined not to wait that

long. They proposed framing a constitution immediately

and submitting it at once to the people regardless of

what the old constitution said. They pointed out that

while some counties in the eastern part of the state had

three or four members to the Legislature the same

population further west had only part of one. The radical

party prevailed and passed a bill for a hurry-up

constitution, which Governor Furnas vetoed. A new bill

was passed which provided for the submission to the

people of the question whether a convention should be

called to frame a new constitution. This could not be

voted upon--under the old constitution--until the fall

election of 1874, when it carried by a vote of 18,067 in

favor to 3,880 against.

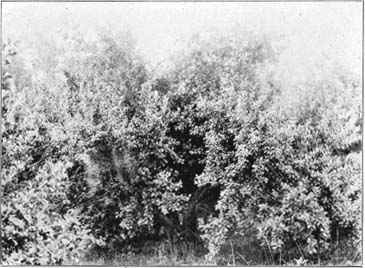

Another cloud appeared

upon the horizon, a cloud of grasshoppers. In July 1874,

the air was suddenly filled with uncounted millions of

the flying insects. Corn fields disappeared from sight

and in their stead stood a dreary waste of little sticks.

The gardens were devoured, fruit trees destroyed and even

railroad trains stopped by this avalanche of locusts. The

sod corn which was the settlers main reliance in the

western part of the state was a complete loss. There was

real destitution in the sod houses and dug-outs along the

border.

The Nebraska Relief and

Aid Society was organized, with Alvin Saunders as

treasurer, and disbursed over $68,000 in relief. Congress

appropriated $130,000 for relief and seed which was

distributed by United States army officers. Bills were

passed permitting homesteaders to leave their claims

without losing them. With