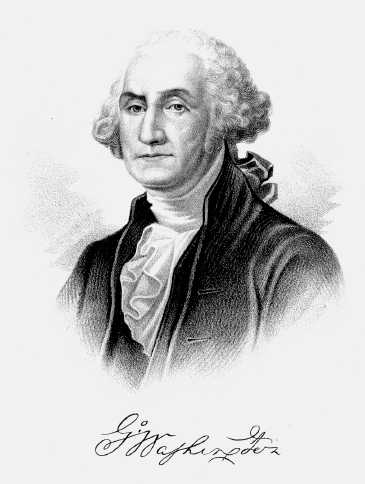

20 GEORGE

WASHINGTON. GEORGE

WASHINGTON.

trip was a perilous one, and several times he came

near losing his life, yet he returned in safety and

furnished a full and useful report of his expedition.

A regiment of 300 men was raised in Virginia and put

in command of Col. Joshua Fry, and Major Washington

was commissioned lieutenant-colonel. Active war was

then begun against the French and Indians, in which

Washington took a most important part. In the

memorable event of July 9, 1755, known as Braddock's

defeat, Washington was almost the only officer of

distinction who escaped from the calamities of the day

with life and honor. The other aids of Braddock were

disabled early in the action, and Washington alone was

left in that capacity on the field. In a letter to his

brother he says: "I had four bullets through my coat,

and two horses shot under me, yet I escaped unhurt,

though death was leveling my companions on every

side." An Indian sharpshooter said he was not born to

be killed by a bullet, for he had taken direct aim at

him seventeen times, and failed to hit him.

After having been five years in the

military service, and vainly sought promotion in the

royal army, he took advantage of the fall of Fort

Duquesne and the expulsion of the French from the

valley of the Ohio, to resign his commission. Soon

after he entered the Legislature, where, although not

a leader, he took an active and important part.

January 17, 1759, he married Mrs. Martha (Dandridge)

Custis, the wealthy widow of John Parke Custis.

When the British Parliament had

closed the port of Boston, the cry went up throughout

the provinces that "The cause of Boston is the cause

of us all." It was then, at the suggestion of

Virginia, that a Congress of all the colonies was

called to meet at Philadelphia, Sept. 5, 1774, to

secure their common liberties, peaceably if possible.

To this Congress Col. Washington was sent as a

delegate. On May 10, 1775, the Congress re-assembled,

when the hostile intentions of England were plainly

apparent. The battles of Concord and Lexington had

been fought. Among the first acts of this Congress was

the election of a commander-in-chief of the colonial

forces. This high and responsible office was conferred

upon Washington, who was still a member of the

Congress. He accepted it on June 19, but upon the

express condition that he receive no salary. He would

keep an exact account of expenses and expect Congress

to pay them and nothing more. It is not the object of

this sketch to trace the military acts of Washington,

to whom the fortunes and liberties of the people of

this country were so long confided. The war was

conducted by him under every possible disadvantage,

and while his forces often met with reverses, yet he

overcame every obstacle, and after seven years of

heroic devotion and matchless skill he gained liberty

for the greatest nation of earth. On Dec. 23, 1783,

Washington, in a parting address of surpassing beauty,

resigned his commission as commander-in-chief of the

army to to (sic) the Continental Congress sitting at

Annapolis. He retired immediately to Mount Vernon and

resumed his occupation as a farmer and planter,

shunning all connection with public life.

In February, 1789, Washington was

unanimously elected President. In his presidential

career he was subject to the peculiar trials

incidental to a new government; trials from lack of

confidence on the part of other governments; trials

from want of harmony between the different sections of

our own country; trials from the impoverished

condition of the country, owing to the war and want of

credit; trials front the beginnings of party strife.

He was no partisan. His clear judgment could discern

the golden mean; and while perhaps this alone kept our

government from sinking at the very outset, it left

him exposed to attacks from both sides, which were

often bitter and very annoying.

At the expiration of his first term

he was unanimously re-elected. At the end of this term

many were anxious that he be re-elected, but he

absolutely refused a third nomination. On the fourth.

of March, 1797, at the expiraton (sic) of his second

term as President, he returned to his home, hoping to

pass there his few remaining years free from the

annoyances of public life. Later in the year, however,

his repose seemed likely to be interrupted by war with

France. At the prospect of such a war he was again

urged to take command of the armies. He chose his

subordinate officers and left to them the charge of

matters in the field, which he superintended from his

home. In accepting the command he made the reservation

that he was not to be in the field until it was

necessary. In the midst of these preparations his life

was suddenly cut off. December 12, he took a severe

cold from a ride in the rain, which, settling in his

throat, produced inflammation, and terminated fatally

on the night of the fourteenth. On the eighteenth his

body was borne with military honors to its final

resting place, and interred in the family vault at

Mount Vernon.

Of the character of Washington it is

impossible to speak but in terms of the highest

respect and admiration. The more we see of the

operations of our government, and the more deeply we

feel the difficulty of uniting all opinions in a

common interest, the more highly we must estimate the

force of his talent and character, which have been

able to challenge the reverence of all parties, and

principles, and nations, and to win a fame as extended

as the limits of the globe, and which we cannot but

believe will he as lasting as the existence of

man.

The person of Washington was

unusally (sic) tan, erect and well proportioned. His

muscular strength was great. His features were of a

beautiful symmetry.

He commanded respect without any

appearance of haughtiness, and ever serious without

being dull.

|