![]()

OLD CATSKILL

Written by Henry Brace

from

Harper's New Monthly Magazine

No. 360

May 1880

Pages 810 to 826

Published by

Harper & Brothers,

Franklin Square, New York

Kindly Contributed by Linda Van Deusen-Kintzing

10 March 2004

transcribed by Susan Stalker Mulvey

Page 810

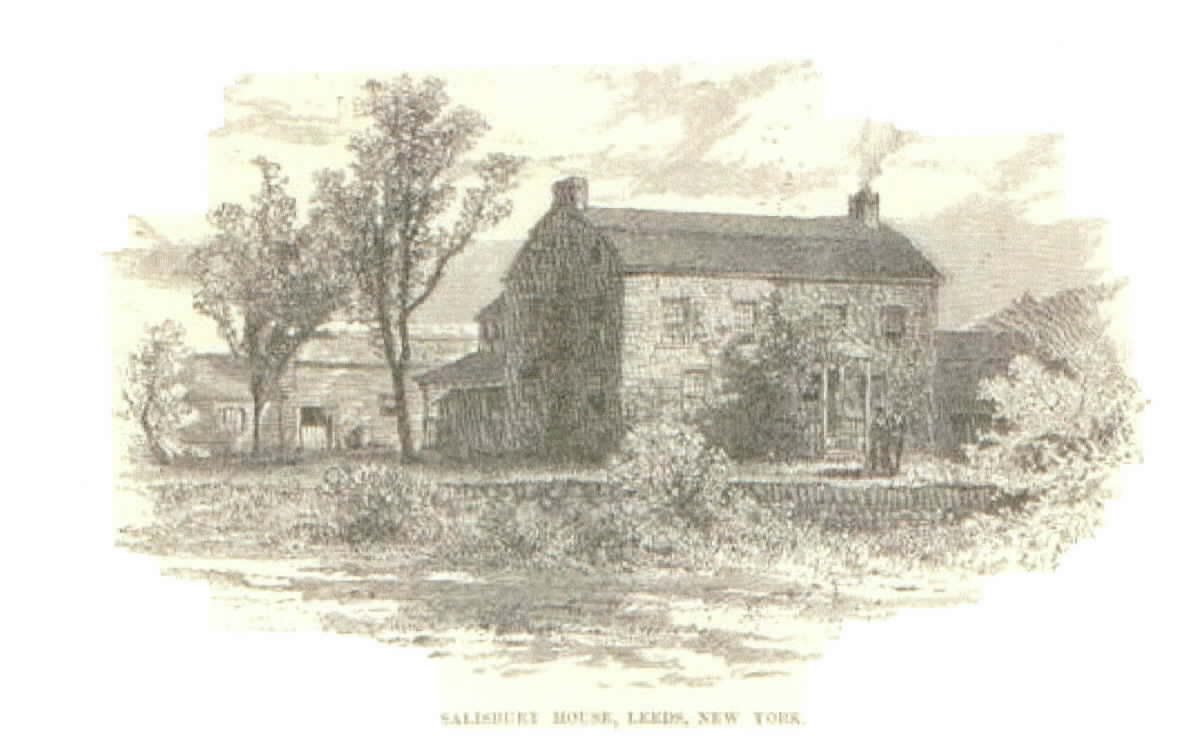

Salisbury House, Leeds, New York

Four miles from the village of Catskill, upon the right bank of the river of the name, lies an alluvial plain of several hundred acres. This plain is raised a few feet above the usual level of the water, by which, however it is covered, and also enriched in times of flood. A continuous hillock like a terrace encompasses this fertile tract. Beyond the hillock are the Potick Mountains, and the precipitous range of Hamilton shales, which the Dutch called the Hoogeberg. This region--the plain, hillock, and adjacent land--a hundred years ago went by the name of Catskill, the site of the village of that name upon the Hudson being known as T' Strand, or The Landing.

In the early days of the Dutch supremacy the plain and the terrace around the plain were the dwelling-place of the tribe of about three hundred Indians. They were of Algonkin lineage, but whether their totem, or national symbol, was the wolf of the Delawares, or the wolf of the Mohicans, is a question which has been discussed by antiquarians, but which has not been determined. In later times, however, toward the close of the seventeenth century, the tribe became a mixed race of Mohicans, Delawares, Pemacooks, refugees from Connecticut, and Nanticokes, refugees from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Their sachem was Mahak-Nemiaw, whose name often occurs in the ancient records of the province. He was the type of his race. He was lazy and shiftless, and earned a precarious living by hunting and trapping. He liked to attend before the Council of the province at Albany, where he and his fellow-sachem, Keesje Wey, could talk about the great Father across the water, and about keeping the chain of friendship bright, and receive in return long strings of wampum, woollen shirts, and gunpowder. He was fond of beer, when he could not get brandy, and steadfastly resisted every attempt which was made to civilize and to convert him. The last one hears of this noble savage is in 1682, when his brethren sold the remaining parcel--an estate of nearly four thousand acres--of his and their domain upon the Catskill. It is provided in the deed of purchase that Mahak- Neminaw, sachem of Catskill, not being present at the transfer, shall have so soon as he comes home, two pieces of duffers and six cans of rum.

The site of old Catskill was well chosen. Upon the terrace, out of the reach of the highest floods of the river, were the wigwams, the fortress, and the burying-ground of the Indians. The forests abounded with game. The river and its beautiful tributaries were full of fish. A portion of the lowlands, cleared by the [page 811] slow process of burning down the trees, was tilled by the women with easy labor, and brought forth an abundant store of maize, beans, and pumpkins. If during the long winter the native occupants of this tract sometimes went hungry to the point of starvation, it was due to their child-like want of forethought and to their shiftless improvidence.

The purchasers of the plain, with the surrounding territory for four miles in every direction, were Marten Gerritsen Van Bergen, komissarie, justice of the peace, and ruling elder in the Dutch church at Albany, and Silvester Salisbury, captain in the British army, and commander of his Majesty's forces. On the 8th of July, 1678, the bargain was consummated with unusual formality, at the Stadt Huis at Albany, before Robert Livingston, secretary of the Council, and in the presence of the magistrates of the jurisdiction, and of a motley group of Catskill and Mohican Indians. Mahak-Neminaw and his six head-men, as representatives of the whole tribe, executed with rude and hieroglyphic signatures a deed of their great domain, and gave formal possession to the buyers. The sellers no longer had a permanent dwelling-place. Whither they went, or what their fate was, is no longer known. They, their chief alone excepted, are not again spoken of in any record of the province. The tradition, however, remains that in the time of our grandfathers a little band of Indians were wont to come every summer from their home beyond the Mohawk, and encamp in a grove of chestnut-trees at the northern edge of the plain. They asserted that their forefathers once owned the lowland near by.

Van Vechten's House--[See page 826]

Neither Salisbury nor Van Bergen lived upon their estate at Catskill. But their sons, when they had grown up, left Albany, and took up their residence upon their patrimony. It was a transfer which brought to them serious loss of social and religious opportunities. They banished themselves in a great measure from the society of the Rensselaers, the Livingstons, the Van Schaicks, and the Ten Broecks; they gave up the ministry of Domine Schaets; they put themselves out of the line of appointment as magistrates of the city. Their new homes was in a wilderness.

The house which Francis Salisbury built for himself upon his share of the domain is still standing, as sound in foundation, walls, and roof beams as on the day, one hundred and seventy-three years ago, when it was finished. It was once the largest and most costly house between Newburgh and Albany. It is two stories high, about fifty feet wide, and about thirty-five feet deep. Its massive walls are of sandstone, which was quarried from ledges in the neighborhood, and are pierced on either story with loop-holes, narrow on the outside and wider on the inside--a lively memento of days long since gone by, when the yeomen of the upper valley of the Hudson live in terror of [page 820]

![]()

![]()