THE WORLD'S STUPENDOUS GRANARY

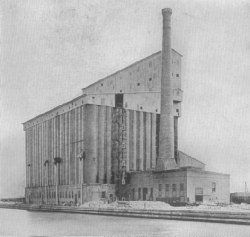

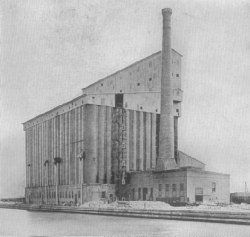

| A mammoth grain elevator—"The

Great Northern," at Duluth. |

Fifteen million barrels of flour is the annual output of the world's greatest granary, at Minneapolis. For some time this city of the Northwest has been recognized as the largest primary wheat market of the world, and also the greatest milling center.

Thousands of persons make annual trips to Minneapolis to see the great mills, and observe the process by which several trainIoads of wheat are turned into flour in one day. But the methods of flour making have undergone so many radical changes within the past few years that men who were once experts, in the business would now be novices.

GREAT INCREASE IN CAPACITY OF FLOURING MILLS.

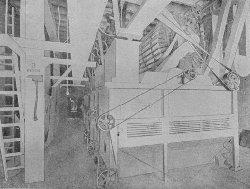

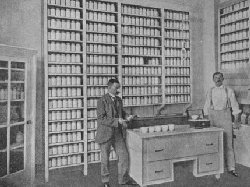

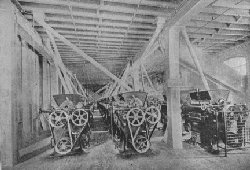

| Dust collectors and purifiers,

Pillsbury "A" Mill. |

The number of flouring mills in Minneapolis is no greater than it was 20 years ago, but the present annual output of 15,000,000 barrels exceeds that of 20 years ago by more than 650 per cent, and this in the face of the fact that some of the larger plants manufacture, in addition to their flour product, immense quantities of the different kinds of breakfast cereals now so commonly used. The gain in capacity is due to the fact that most of the mills have been enlarged from time to time and equipped with the very best modern machinery.

LARGEST FLOUR MILL IN THE WORLD.

As an illustration, the Pillsbury mill was constructed in 1880 with a daily capacity of 5,000 barrels, but it has been improved until its capacity is now 14,000 barrels. This is the largest flour mill in the world.

MECHANICAL PROCESSES OF A GREAT FLOUR MILL.

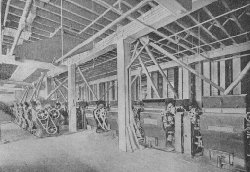

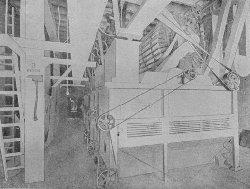

| Grinding flour, Pillsbury

"A" Mill. |

The flour mills of the present are a wonderful triumph of scientific industry, and when in full operation one of them seems almost a thing of life. The wheat is shoveled by machinery from the car into a large pit, from which it is taken into the endless machinery of the mill. It is then hurried on, this way and that, through secret passages, from one side of the big mill to the other, now up, now down, through this machine and that, until finally every kernel is divided into as many component parts as the processes number, and each part drops into its own receptacle. It has been forced through all these by the mill's own machinery, without having been touched by human hands or seen by human eyes. No one is watching to see if it takes the proper course, or if any part of the machinery does its work; a lever is pulled which conducts a portion of the Mississippi upon a big wheel, and all the intricate machinery in the giant mill responds with a harmony that seems almost human.

DECREASE IN PRICE OF FLOUR,

| By courtesy of the

"Scientific American."

Baking bread in electric ovens. |

Incidentally it may be mentioned that while the mills have been increasing their capacity and improving their processes the price of the product has been steadily decreasing. In 1880 the average profit on a barrel of flour was about 75 cents, while now the millers think themselves fortunate when they figure up their profits and find that about 20 cents is realized after all expenses have been paid.

It must not be inferred from this that the business of milling has reached a crisis, or that the meager profits on a barrel of flour, as compared with those of the early days, have affected the milling industry. The price of flour has been reduced through natural causes, but the reduction has been, perhaps, more than offset by the increased capacity of the mills through the introduction of modern machinery. The lucrativeness of all the large manufacturing industries to-day depends upon the great volume of the output rather than upon the large percentages of profit.

THE NEW MONSTER ELEVATORS.

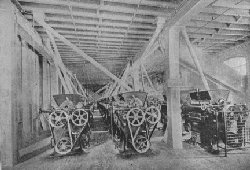

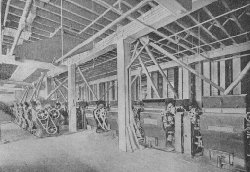

| | Griding flour, Pillsbury "A" Mill. |

Twenty years ago a car carried about four hundred bushels, but those now being built carry twelve hundred bushels. The building of new roads and improvements in methods of transportation have also reduced the price of grain carrying to terminal points in Minnesota nearly, if not quite, 66 per cent. But little more than ten years ago it cost twenty-six cents a hundred pounds to ship wheat from Minneapolis to Chicago; to-day the same amount is carried for ten cents. Twenty years ago it cost from 15 to 18 cents a bushel to ship wheat from Duluth to Buffalo; to-day a rate of three cents a bushel would be excessive. At that time a good cargo was 30,000 bushels; now those figures may be multiplied by ten. A great grain market, created and fostered by an extensive system like that at Minneapolis, has made a radical change in the problem of storage construction.

THE MODERN TERMINAL ELEVATOR.

The modern terminal elevator, which is a child of necessity, has reached its present development through as many evolutions, perhaps, as those of the modern flour mill. There has been no change in recent years in the methods of operating a terminal elevator, except that in some cases electricity has been substituted for steam as power, and that in a few instances, the grain is conveyed by pneumatic tubes instead of by cup-belts. But the shape and material of the structures have been completely revolutionized. Some years ago, in this process of evolution, steel began to supplant wood as building material, and the Great Northern steel elevator of Duluth, which is capable of storing more grain under one roof than any other elevator in the world, is made wholly of steel.

OUTSIDE STORAGE TANKS.

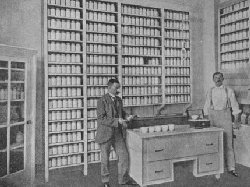

| | Testing samples of flour, Pillsbury Mills. |

Cylindrical tanks for storage next began to be erected outside of and separate from the elevator, instead of the long bins in the elevator proper. Some are made of steel, some of tiling and some of cement. A wide, flat, rubber belt carries the grain from the upper story of the elevating plant, or working house, to the tanks, and discharges it through a hole in the roof. When grain is shipped from a tank it is conveyed from the bottom of the structure through a subterranean passage to the elevator pit on a belt similar to the overhead belt which carries it to the tank. From the pit it is elevated to the shipping floor and spouted to a car.

It is possible to keep grain making this circuit continuously, from the pit to the top of the "working house" by the cup-belt to the top of the tank by the horizontal belt, to the bottom of the tank by gravitation, and then to the elevator pit again by the underground passage. Somtimes, damp gain is treated in this way to dry it. A conveying belt is three feet wide, and the stream of grain which falls upon its surface is from Six to seven inches in diameter. A six-inch stream will empty a tank of about five thousand bushels of wheat in an hour. Each plant consists of a dozen of these tanks, more or less, and their capacity is about 100,000 bushels each. These are much more expensive than the old-style houses, but the extra expense is offset in a few years' time by the saving in insurance. Being strictly fireproof no insurance is carried on the structure or its contents. Thus, while the mills have passed from the primitive to the modern era, and the methods of transportation have been improved, the elevators have kept pace with these improvements.

STATE SUPERVISION OF TERMINAL GRAIN MARKETS.

| Pillsbury "A" Mill, the largest flour

mill in the world.

Capacity, 15,000 barrels daily. |

In addition to the great industries already mentioned, Minnesota has a system of state supervision over the grain market at its terminal elevators, in which the grain dealers of the whole world are vitally interested. Other states adopt similar measures, but do not compare in efficiency with this big cereal state of the northwest. Certificates issued by Minnesota are accepted without question. In Illinois, the elevators are regulated by state commissioners.

The Grain Production of the United Staes, in Bushels, for Certain years, is as Follows:

| | Indian Corn | Wheat | Oats | Barley | Rye |

| 1890 | 1,489,970,000 | 339,262,000 | 532,621,000 | 67,168,344 | 25,807,472 |

| 1895 | 2,151,138,580 | 467,102,947 | 824,443,537 | 87,072,744 | 27,210 070 |

| 1900 | 2,105,102,516 | 522,229,505 | 809,125,989 | 58,925,833 | 23,995,927 |

| 1901 | 2,111,107,411 | 531,645,723 | 811,745,654 | 59,634,156 | 23,756,435 |

| 1902 | 2,412,110,376 | 533,472,076 | 812,465,000 | 60,474,001 | 24,656,374 |

From the following table, taken from the "Year Book of the Department of Agriculture," may be seen the relative food values possed by various grades of flour, together with the refuse matter.

| Components | High-grade

patent flour | Bakers' flour | Common

market flour | Flour of

small mills |

|---|

| Water | 12.75 | 11.75 | 12.25 | 12.85 |

| Proteids | 10.50 | 12.30 | 10.20 | 10.30 |

| Ether Extract | 1.00 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.05 |

| Ash | .50 | .60 | .90 | .50 |

| Moist Gluten | 26.00 | 34.70 | 24.50 | 26.80 |

| Dry Gluten | 10.00 | 13.10 | 9.25 | 10.20 |

| Carbohydrates | 75.25 | 74.05 | 75.65 | 75.30 |

From the same authority are tabulated the following figures pertaining to a representative brand of self-rising flour.

| Components | Self-rising

flour | High-grade

patent flour | Bakers' flour |

|---|

| Water | 12.30 | 12.75 | 11.75 |

Proteids

(factor 6.25) | 10.10 | 10.50 | 12.30 |

| Moist Gluten | 27.00 | 26.00 | 34.70 |

| Dry Gluten | 9.65 | 10.00 | 13.10 |

| Ether Extracts | .70 | 1.00 | 1.30 |

| Ash | 4.00 | .50 | .60 |

| Carbohydrates | 72.90 | 75.25 | 74.99 |

RAILWAYS, THE ARTERIES OF COMMERCE

THE "SOO'S" GREAT POWER CANAL

Table of Contents

Return to Main Page

© 1998, 2002 by Lynn Waterman

|