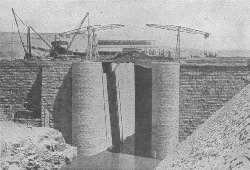

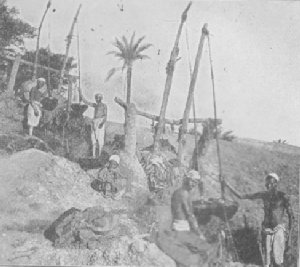

One gains a clearer idea of the magnitude of the task by recalling the first step taken; that was, to divert the channel and excavate in the rocky river-bed a trench one hundred feet wide and as many feet deep, in which to lay a concrete foundation for the massive piers. At its best, and controlled, the Nile is very generous, as befits the majesty of its three thousand miles. Joseph the Israelite drew some of his prosperity from it. One of the irrigation canals he planned for Pharaoh's people is still in use. But in most moods the Nile is a sullen and inconstant stream, and even in the days when Egypt was the granary of imperial Rome there seems to have been no comprehensive attempt to govern it.

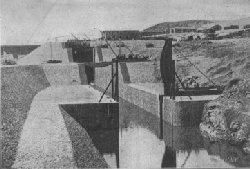

The most important of the worksconstructed to enable the water stored up in the great reservoir to be utilized to the greatest advantage is the barrage across the Nile at Assiout, about 250 miles above Cairo, which was commenced by Sir John Aird & Company in the winter of 1898, and completed in 1902. In general principle this work resembles the old barrage at the apex of the delta; but in details of construction there is no similarity, nor in material, as the old work is of brick and the new one is of stone. The total length of the structure is 2,750 feet, or rather more than half a mile, and it includes 111 arched openings of 16 four-inch spans, capable of being closed by steel sluice-gates 16 feet in hight. The object of the work is to improve the perennial irrigation of lands in Middle Egypt and the Fayoum, and to bring an additional area of about 300,000 acres under such irrigation by throwing more water at a higher level into the great Ibrahimick Canal, the intake of which is immediately above the barrage.

The first channel was successfully closed on May 17, 1899, the depth being about 30 feet and the velocity of the current about 1.5 miles an hour. In the case of another channel, the closing had to be helped by tipping in railway wagons themselves, loaded with heavy stones and bound together with wire ropes, making a weight of about 50 tons—this great mass being necessary to resist displacement by the torrent. These rubble dams were well tested when the high Nile ran over them; and on work being resumed in November, after the fall of the river, water-tight sand-bag dams, or "sudds," were made around the site of the dam foundation in the still waters above the rubble dams, and pumps were fixed to lay dry the bed of the river.

The masonry of the dam is of local granite, set in British, Portland-cement mortar. The interior is of rubble set by hand with about 40 per cent of the bulk in cement mortar, four parts of sand to one of cement. All the face work is, of course, rock-faced ashlar, except the sluice linings, which are finely dressed. The maximum number of men employed on this dam was 11,000.

Moreover, the old canals and the dams at the delta barely touched the surface of Egypt's irrigation problem, the problem of avoiding drouth and making waste lands fertile. The great dams at Assouan and Siut, "inaugurated" in the summer of 1903, go to the bottom of things in more than one sense of the word. At Assouan, near the First Cataract, nearly six hundred miles from Cairo, the Nile is a mile wide. The dam is a quarter-mile wider, a great granite wall that rises ninety feet above the level of low Nile, and is sixty feet wide at the top. When the river is in flood, its waters gush through one hundred and eighty massive sluice-gates. In autumn the sluice-gates are closed until the reservoir thus formed is full, ready to be distributed through canals and ditches over the agricultural land on either side. In April and August, when the water is most wanted for the crops, the supply in the lower river is increased from the reservoir. At Siut, about half-way between Assouan and Cairo, is a subsidiary dam a half-mile wide, with more than one hundred sluice-gates. Broadly speaking, the two reservoirs add $400,000,000 in land values to the region covered by their operation. 1Total length, 1¼ miles; maximum height above foundation, 130 feet; difference of water level above and below, 67 feet. Total weight of masonry, over 1,000,000 tons. Return to text. OLIVE CULTURE ON AN EXTENSIVE SCALE |