138. The Beginnings of Trouble. When the English sidiers and sailors came back from fighting in Holland, they told their queen and people horrible tales of Spanish cruelty. Likewise, the sailors from the New World told how the Spanish had captured English sailors and had burned them at the stake.

These stories set the British seamen on fire for  revenge. King Philip of Spain sent threats of what he would do, but no attention was given them while English sailors felt that their fellows were flung into Spanish dungeons "laden with irons, without sight of sun or moon."

revenge. King Philip of Spain sent threats of what he would do, but no attention was given them while English sailors felt that their fellows were flung into Spanish dungeons "laden with irons, without sight of sun or moon."

139. Sir Francis Drake. The most famous of the sea captains who came to the help of England against Spain was Sir Francis Drake. He had served many years under a kinsman, a daring sailor, Sir John Hawkins, a slave trader and a member of Parliament. Drake was serving under Hãwkins when he lost all, except his honor and his courage, in a sea fight:

The queen gave Sir Francis Drake command of a vessel, and in company with two other ships he captured a Spanish town on the Isthmus of Panama, and from the top of a tree beheld the blue waters of the Pacific. He resolved to sail its waters some day.

So pleased was Queen Elizabeth with the way in which Drake made use of the Spanish wealth he had obtained,that she gave him the money for his new expedition against the Spaniards. There was great excitement in England when it became known that Drake was to go in search of Spanish treasure ships in the Pacific.

140. The First Englishman to Circumnavigate the Globe. With four ships Drake made direct for the Strait of Magellan. He lost two of the ships, and one returned home, but Drake kept on in the Pelican, which he renamed the Golden Hind. On the western coast of South America he spied the treasure ships, gave chase, and soon overtook them with his smaller and fleeter boat. He loaded her to his heart’s content with the gold, silver, and precious stones the Spaniards had gathered in Peru.

Drake was wise. He sailed north to the coast of what is now California, and spent the winter there repairing his vessel, resting, and searching for a northeast passage to the Atlantic. He knew the Spaniards were waiting his return, so he turned the prow of the Golden Hind to the westward, sailed through the Indian Ocean, and reached home in a little less than three years (1580).

Drake had circumnavigated the world—the first Englishman to do it—and had brought great wealth home to England. Queen Elizabeth went on board his ship, with lords and ladies, and conferred knighthood upon Drake as a reward for his great achievements.

When the story of the doings of Drake was told King Philip, he was angry indeed, and resolved to strike a counter blow that England would have good cause to remember; not only a blow for Drake’s acts, but in revenge for the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, which had just taken place in the Tower.

141. "Singeing the Spanish King’s Beard." The King of Spain had been working hard for three years. All Spain was busy with preparations. Something must be done, and that quickly. Elizabeth sent Drake with thirty small vessels to make an attack. He reached Cadiz, sailed right into the harbor, burned store ships and ships for carrying troops, and escaped without harm. It took the King of Spain another year to get ready!

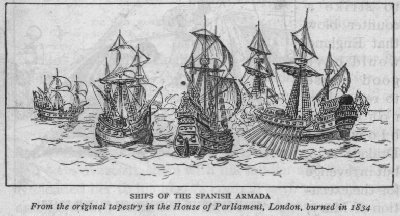

142. The Coming of the Great Armada (1588). If Philip was angry before, he was furious now. He made greater preparation than ever. But the people of England were ready, too. The national enthusiasm was raised to the highest pitch, and Catholics as well as Protestants joined the army and navy to defend "Good Queen Bess."

When the news came that the Spanish fleet had entered the English Channel, signal fires burned from every hilltop along the coast. The story is told that Lord Howard, Sir Francis Drake, and other English sea captains were busy on shore with a game of "bowls"

when the alarming news reached them. Howard was in favor of putting to sea at once. But Drake replied: "There‘s plenty of time to win this game, and thrash the Spaniards, too."

The English ships were fewer in number than the Spanish, but were better built, faster sailers, and manned by more skillful sailors and experienced captains. The Englishmen, too, were better marksmen than the Spaniards.

143. A Great Sea Fight. There were thousands of soldiers on board the Spanish ships, with which to invade England. Up the Channel the mighty fleet came, past the English town of Plymouth, where the game 9f bowls was being played. Now the English sailors "cleared the decks" of their swifter warships, dashed in, and pounced upon one Spanish vessel at a time. In this wise they chased the Armada into the French port of Calais.

The Spaniards were hoping to carry still other soldiers from the Netherlands, where they had been fighting the Dutch, to the invasion of England, but they soon had other things to think of, for the English sent "fire ships" drifting among the vessels of the Armada.

When the Spaniards saw certain destruction floating down upon them they lifted their anchors and sailed out to sea again, where the English could get at them. Hard fighting followed, and the Armada sought to escape by sailing around to the north of Scotland and Ireland, but terrible storms overtook them. Scores were dashed to pieces and thousands of sailors and soldiers lost their lives. In a walk of five miles along the Irish coast an Englishman reported that he had counted more than a thousand dead Spaniards.

144. A Crushing Defeat. After the defeat of the Armada all Spain was in mourning, for almost every noble family lost a son. King Philip tried to excuse his great sea captain who commanded the fleet, by saying, "I sent you to fight against men, and not with the winds."

In the minds of the English, Drake, Howard, and the other ship commanders were great heroes. The powerof Spain was broken. Gradually, on land and sea, her forces grew feebler, until she gave up her position as leader in Europe. In the SpanishAmerican War Spain lost her last great possessions in the West and East Indies to the United States.

145. How Sir Walter Raleigh Won the Queen’s Favor. One of the bravest men who fought for the glory of England against the Spanish Armada was Sir Walter Raleigh, born in 1552. He had joined the English forces sent to help William the Silent, and had seen service in Ireland. At thirty years of age he was striking in his looks, tall, straight, and handsome. He was a polished man, full of wit and humor.

One day Raleigh stood aside with the crowd which always gathered to see the queen and her fine lords and ladies go by. The queen hesitated at a muddy place. In a moment Raleigh had thrown his red plush coat down for the queen and her ladies to step upon. Raleigh’s reward was a nod and a smile from her gracious Majesty. From now on he was a great favorite at court.

146. Raleigh Tries to Plant Colonies in America. Raleigh found the planting of colonies a better way of opposing the power of Spain in America than robbing treasure ships or burning her cities. He had accompanied his  half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on two voyages to America. Gilbert was the first Englishman to attempt to plant a colony in the New World. His efforts had failed because the people who went with him were mainly adventurers who had no desire to settle down to the hard task of developing a new country. They wanted gold mines which would quickly transform them into rich men, so that they might return to England and live the lives of gentlemen. Gilbert himself was a noble man and had great faith in the future colonization of America. Compelled to abandon his plans, he sailed for home, but his boat was wrecked in a heavy storm and all on board perished. Raleigh, who strongly believed in the colonization plan, now obtained permission from the queen, and immediately sent Amidas and Barlow to the New World. They brought back such charming stories of land, climate, and Indians that Elizabeth gave the region from Maine to Mexico the name Virginia in honor of her own virgin life.

half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on two voyages to America. Gilbert was the first Englishman to attempt to plant a colony in the New World. His efforts had failed because the people who went with him were mainly adventurers who had no desire to settle down to the hard task of developing a new country. They wanted gold mines which would quickly transform them into rich men, so that they might return to England and live the lives of gentlemen. Gilbert himself was a noble man and had great faith in the future colonization of America. Compelled to abandon his plans, he sailed for home, but his boat was wrecked in a heavy storm and all on board perished. Raleigh, who strongly believed in the colonization plan, now obtained permission from the queen, and immediately sent Amidas and Barlow to the New World. They brought back such charming stories of land, climate, and Indians that Elizabeth gave the region from Maine to Mexico the name Virginia in honor of her own virgin life.

Raleigh immediately sent out a fleet under Ralph Lane as governor (1584), but instead of working to raise a supply of food, they spent the time searching for gold and silver. Sir Francis Drake, returning from the West Indies, brought the colonists back to England. But this colony did some good in the world: it carried to England the tobacco plant—which afterwards became the basis of Virginia’s prosperity—and the white potato, which has been worth more to the world than all the gold found by Cortés and Pizarro.

A second colony of one hundred and fifty men and women was sent. John White, the governor, had to return to England for supplies. But at that time all England was rising to meet the Armada. Men’ were needed at home, and it was almost three years before he sailed back, to find the colony gone, no one knew where. Raleigh searched in vain for his lost colony.

Raleigh’s purse was not equal to his courage. His money was soon gone. No one man had enough to found a settlement, and finally when Virginia was settled it was done by a great chartered company. But Raleigh declared that he would live to see the day when Virginia would be a nation. He did live to see the day when a vessel, carrying the products of Virginia, had sailed into an English port, and an Indian princess, Pocahontas, had married an Englishman and had been received by the king and queen of England.

147. The Meaning of the Battle with Spain. For nearly one hundred years France, Holland, and England had been battling with the Spaniard. Sometimes it was a trial at arms on the battlefields of Europe, at other times a conflict between sailors for the control of the seas. But every war that was fought meant the gradual but growing weakness of Spain. By the time Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620) were settled, English sailors felt that in courage and skill they were more than a match for the sailors of Spain.

After Virginia had been settled over half a century, some English noblemen settled the Carolinas. Spain looked upon this movement as threatening her colonies in Florida, and retaliated by attacking the Carolinas. In the course of time Englishmen demanded that the colony of Georgia be planted as an outpost against the Spaniards. A great man in England combined a plan of settling Georgia with men imprisoned for debt, with the scheme of making the colony a bulwark against Spain. Fredericka, a place in southern Georgia, was soon fortified and bravely withstood all attacks of the Spaniards.

148. France and England Fight for Control. We saw the Dutch plant the colony of New Netherland. A number of Dutch governors ruled it, but in 1664 it came, by conquest, into the hands of the English. Thus England had a continuous line of colonies from Maine to Georgia.

The French were pushing their claims to the St. Lawrence region. The fur trader and the missionary were steadily making their way westward to the Mississippi. A little later the French began to move from the Gulf of Mexico up the Mississippi. By 1750 France had a complete chain of forts from gulf to gulf, joining the St. Lawrence, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi.

England took alarm. The wars of King William, Queen Anne, and King George were only skirmishes compared to the great French and Indian War (1752— 1763). But in this war France was beaten, and England ruled North America east of the Mississippi River.

It does not require a big stretch of the imagination to see the Spanish-American War (1898) as the dying effort of Spain to retain control of her colonies in the West Indies and in the Philippines. Once Europe bowed to her might in war, and in America she seemed in a fair way to swallow up the best parts of the New World, but in our day she ranks among the smaller nations of the world. Thousands of her best men, millions upon millions of money, and millions of square miles of the richest land the sun ever shone upon, Spain wasted in war. War has its lessons, but Spain was too slow to learn.

SUGGESTIONS INTENDED’TO HELP THE PUPIL

The Leading Facts. 1. Drake hated the Spaniards. 2. He sailed to the Pacific in the Pelican and then turned northward after the Spanish gold ships. 3. He wintered in California, and then started across the Pacific, the first Englishman to sail around the world. 4. Drake reached England, and was received with great joy. 5. Once more Drake went to fight Spaniards, until the Great Armada attacked England. 6. The size and purpose of the Armada. 7. Prove that Drake was not alarmed. 8. How the English beat the Armada. 9. A battle between Teuton and Latin. 10. Walter Raleigh, a soldier, won the favor of the queen. 11. He hated the Spaniards, and planted settlements in what is now North Carolina. 12. Raleigh’s prophecy. 13. Final result of Raleigh’s efforts to settle America. 14. The struggle with France.

Study Questions. 1. What reason had the Spaniards for thinking Drake a dragon? 2. Tell the story of Drake’s circumnavigation. 3. How did Queen Elizabeth reward him? 4. Why did Drake sail into the port of Cadiz and "singe the king’s beard"? 5. Where is Cadiz? 6. Explain the double purpose of the Armada. 7. How did the Spaniards expect to get so!diers in the Netherlands? 8. How did the English beat the Spaniards? 9. How did the defeat of the Armada injure Spain and help England, France, and the Netherlands? 10. What experiences did Raleigh have before he was thirty years old? 11. Make a picture of the cloak episode. 12. How did Raleigh plan to check the power of Spain? 13. What did the colonists take home with them? 14. What was the reason for the failure of Raleigh’s last settlement in America? 15. Tell about the final struggle between France and England.

Suggested Readings. DRAKE: Hart, Source Book of American History, 9-11; Hale, Stories of Discovery, 86-106; Frothingham, Sea Fighters from Drake to Farragut. THE ARMADA:

Warren, Stories from English History, 234-241; Bacon, The Boy’s Drake, 3-470; Church, Stories from English History, 244-260. RALEIGH: Hart and Hazard, Colonial Children, 166-170; 7p; Wright, Children’s Stories in American History, 254-258 Higginson, Young Folks’ Book of American Explorers, 177-200; Bolton, Famous Voyagers, 154-234; Blaisdell, Stories from English History, 112-124.

Next Chapter

Back to Table of Contents.

© 2001 by Lynn Waterman