THROUGH THE ROCKIES TO THE PACIFIC

Ascending the Jefferson. Reaching the Great Divide. Some friendly Indians. Sacajawea meets old acquaintances. Hardships and disappointments. Struggling across the mountains. Among the Nez Percés. On toward the sea. Passing the cataracts of the Columbia. The first glimpse of the sea.

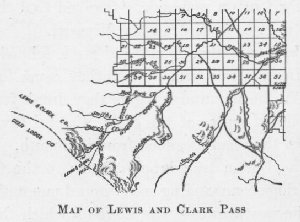

It was on the 30th of July that they began the laborious ascent of the Jefferson, or true Missouri. Captain Lewis went ahead to find some Indians and gain information as to the way across the mountains. The others followed, struggling with rapids and shoals, often wading through the water over slippery stones and dragging the boats, and often puzzled as to the right course by the bewildering forks of the stream. On August 11 Lewis saw a Shoshone on horseback, whom he tried vainly to attract by holding up a looking-glass and beads and making friendly signs. Lewis was now traveling near the base of the Bitter Root Mountains, hoping to find an Indian trail leading to a pass. As he kept on, the Jefferson grew smaller and smaller, until it dwindled to a brook, and one of the men, with a foot on each side, "thanked God that he had lived to bestride the Missouri."

They had then found and were following an Indian trail, and at last they came to a gap in the mountains where they drank from the actual source of the great Missouri River, which they had ascended from its mouth.

The Indian trail brought them to the top of a ridge commanding snow-topped mountains to the westward. "The ridge on which they stood formed the dividing line between the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The descent was much steeper than on the eastern side, and at the distance of three-quarters of a mile they reached a bold creek of cold, clear water running west, and stopped to taste for the first time the waters of the Columbia."

These were the first white men to cross the "Continental Divide" in our Northwest. In 1792—1793 Alexander Mackenzie had crossed British America to the Pacific.

Lewis and his men kept on to the westward and finally made friends with some Indians.

They smoked the pipe of peace and partook of a salmon, — another proof that they were on the Pacific side of the mountains. The chief promised horses but afterward became suspicious of some treachery, and, between the chief’s changes of mind and scanty food, Lewis’s stay was made most uncomfortable. But at last he and the Indians, with horses, started back to meet Captain Clark, who all this time had been laboriously ascending the Jefferson with the boats.

On August 17, after retracing his course across the divide, Captain Lewis and his party found Captain Clark. As they approached each other the faithful Sacajawea, who was with Clark, began to dance with joy, pointing to the Indians and sucking her fingers to show that they were of her tribe. Presently an Indian woman came to her, and they embraced each other with the most tender affection. "They had been companions in childhood; in the war with the Minnetarees they had both been taken prisoners in the same battle; they had shared and softened the rigors of their captivity till one of them had escaped from their enemies with scarce a hope of ever seeing her friend rescued from their hands."

It was arranged that Clark, with eleven men and with tools, should cross the divide to the village of the Shoshonees. He was then to lead his men down the Columbia and, when he found navigable water, to begin to build canoes. Lewis was to remain and bring the baggage to the Shoshone village. At the council held here the Indians promised to bring more horses, and showed great astonishment at the arms and dress of the men, the "strange looks" of the negro, and the air gun.

On August 20 Clark reached the Shoshone village, which since Lewis’s visit had been moved two miles up the little river on which it was situated. Here he heard most discouraging accounts of the wild country before him and the difficulty of reaching navigable water by which they could descend to the sea. These stories proved too true. Clark passed the junction of the Salmon and Lemhi rivers, where Salmon City, Idaho, is now situated, and he gave the name of Lewis River to the stream below the junction.

The traveling over rocky mountain paths was most trying, and instead of the abundance of game which they had seen in Montana and Dakota there was an absence of deer and other animals. They were obliged to depend largely on such salmon as they could catch, or buy from the Indians. Since the Indians themselves were scant of food, and the white men had no proper fishing tackle, it is not strange that Clark’s followers began, to fear starvation. They explored the Salmon River for fifty-two miles, but saw that progress that way was impossible, and, unsuccessful for once, they returned to join Lewis.

Meantime Lewis had had his own troubles. After promising horses and aid, the Indians threatened to leave him for a buffalo hunt on the eastern side of the mountains, and it was only by much tact and patience that he kept them with him.

On August 30 Clark returned from his unsuccessful search for a water way. A part of the baggage was hidden and the rest was packed on horses. Then the explorers went on slowly through the Bitter Root Mountains. The Indian guide lost his way completely. "The thickets through which we were obliged to cut our way required great labor; the road itself was over the steep and rocky sides of the hills, where the horses could not move without danger of slipping down, while their feet were bruised by the rocks and stumps." They saw no game, and were obliged to resort to horseflesh for food. The nights were cold, and as they reached greater heights the trail was sometimes covered with snow. A few cans of soup and twenty pounds of bear’s oil were all the food that they had left. No wonder that the men grew weak and ill.

But on September 20, half-starved and sick, after nearly three weeks of hardships in the Bitter Root Mountains, they emerged upon a plain where they found Indians and food. At last the barrier of the mountains had been broken through.

These Indians were the Nez Percés. Among the articles of food which they offered were various roots, including the quamash, which was ground and made into a cake called pasheco. This root is still eaten by the Nez Percés, and from quamash comes the name of Camas Prairie. It seemed a relief to have a comparative abundance of food. But this consisted principally of fish and roots, and this strange diet, of which they naturally ate heartily after their privations, caused serious illness throughout the party. "Captain Lewis could hardly sit on his horse, while others were obliged to be put on horseback, and some, from extreme weakness and pain, were forced to lie down alongside of the road for some time."

While resting at the Nez Percé village near the present Pierce City, Idaho, they learned all that they could of the country beyond. The Indian chief Twisted-hair drew a rude map of the rivers, showing the forks of the Kooskooskee, now the Clearwater, the junction with the Snake River, and the entrance of another large river, which was the Columbia.

Late in September, after obtaining provisions from the Indians, they moved on to a camp on the Kooskooskee River. In spite of continued illness they built five canoes. They concealed some of their goods, left their horses with the Indians, and, undaunted by their sufferings, started down the river in their canoes on October 8. One canoe was sunk by striking a rock, and a halt was called to dry the luggage and make repairs. Fish and even dogs were bought from the Indians for food.

Always alert for information, the explorers noted all the peculiarities of their hosts. There were the baths, or sweat houses, which were hollow squares in the river banks, where the bather steamed himself by pouring water on heated stones. Some of the Indians cooked salmon by putting hot stones into a bucket of water until it would boil the fish. Many of them were frightened by the coming of the white men with their guns. At one place Captain Clark, unperceived by them, shot a white crane, and seeing it fall they believed it to be the white men descending from the clouds. When Clark used his burning glass to light his pipe they were more than ever sure that their visitors were not mortal. But they were finally reassured by presents and the kindness and tact which the travelers showed in all their dealings with the savages. There were "almost inconceivable multitudes of salmon" in the rivers. Many at that season were floating down stream, and the Indians were collecting, splitting, and drying them on scaffolds.

One of the first camps was at the junction of the Kooskooskee and Snake, where the city of Lewiston, Idaho, now stands, — named for Captain Lewis. Then, entering the present state of Washington, they descended the Snake, where the wind and the rapids caused various accidents. On October 16 they reached the mighty Columbia, which had been called by the Indians the" Oregon," or "River of the West." This was to be their pathway to the sea.

They were now among the Sokulk Indians, from whom they purchased more dogs, since the salmon were poor and they had accustomed themselves to dog flesh. They noted the deerskin robes of the red men, and their method of gigging (spearing) salmon and drying them; the prevalence of sore eyes among the Indians, ascribed to the glare from the water; and their bad teeth, which they traced to a diet of gritty roots.

On October 23, two days after their first glimpse of Mt. Hood, they reached the first falls of the Columbia, which they passed successfully by portages and by letting the canoes down the rapids with lines. At the next fall they managed, after partially unloading the canoes, to run them down through a narow passage, past a high, black rock, much to the astonishment of the Indians.

Here they were surprised to find that the savages (Echeloots, related to the Upper Chinooks) were living in wooden houses, which consisted in large part of an underground room, lined with wood and covered above ground with a roof composed of ridgepole, rafters, and a white cedar covering. Here, as before, the explorers acted the part of peace-makers, and urged the Indians to cease their warfare with neighboring tribes. Lewis and Clark had before this seen flat-headed women and children in certain tribes, but here the men also had been subjected to this cruel practice. The result was often accomplished by binding a board tightly on an infant’s forehead, and thus flattening it backward and upward.

On October 28 they were visited by an Indian "who wore his hair in a que [cue] and had on a round hat and a sailor’s jacket which he said he had obtained from the people below the great rapids, who bought them from the whites." This was a cheering indication of their approach to the mouth of the Columbia, where the fur trade attracted American and English ships. Later they found an English musket and cutlass and some brass teakettles in an Indian hut, and one of the chiefs had cloths and a sword procured from some English vessel.

Thus they went on through the present Skamania County, Washington, hunting now and then with some slight success, observing the country, buying roots and dogs, and making notes of the habits of the natives and of their burial places, until they came to the "great shoot" or last rapids of the Columbia, which they passed without serious accident.

From Indians below the rapids they heard the encouraging news that three ships had lately been seen at the mouth of the river. As they journeyed toward the sea, the entrance of the Multnomah, now the Willamette River, was concealed from them by the islands at its mouth. A few miles farther up, the prosperous city of Portland, Oregon, now stands. While they were being piloted down the river by the Indian who had come to them in a sailor’s jacket, they caught sight of Mt. St. Helens.

Fog and rain, thievish Indians, and the noises of wild fowl at night were among their smaller troubles, but all were forgotten when, on November 7, the fog suddenly cleared away and "we enjoyed the delightful prospect of the ocean, — that ocean, the object of all our labors, the reward of all our anxieties. This cheering view exhilarated the spirits of all the party, who were still more delighted on hearing the distant roar of the breakers."

Remembering what they had undergone, one can understand their joy at success in their perilous task. They had crossed the continent.

Chapter 16

Back to Legacy

© 2001, Lynn Waterman