It is most fortunate that narratives of this remarkable expedition have come down to us. The best of these was written by Castañeda, who is supposed to have been a well-educated private soldier in Coronado’s army.6

A journey far longer and more perilous than that of Coronado originated in the devotion of the brave priest Fray Juan de Padilla, who was with Coronado, and returned to minister to the Quiviras accompanied only by one soldier, Andrés Docampo, and two boys, Lucas and Sebastian. The good priest was slain in northeastern Kansas. Docampo and the boys wandered over the plains for nine heart-breaking years, sometimes prisoners, sometimes fugitives, finally reaching the Mexican town of Tampico on the Gulf. Their journeyings must have covered thousands of miles of Louisiana territory, but no records have been preserved.7

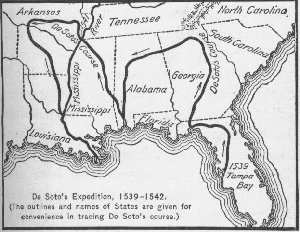

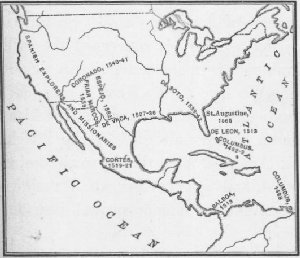

At the same time that Coronado was leading his soldiers eastward, another Spanish officer was struggling from Florida towards the west. This was the famous Fernando de Soto, governor of Cuba, who was commissioned to conquer the unknown territory on the Gulf of Mexico, which had been granted to Narvaez by a royal patent. De Soto sailed from Havana in 1539 and, landing his force of nearly six hundred

men in Florida, fought his bloody way through Georgia and Alabama and on to the Mississippi, which he crossed at Chickasaw Bluff. This was in 1541, and De Soto was the first white man to see the Mississippi except at its mouth.8

After crossing the great river De Soto marched northward to Little Prairie, led by the vague tales of gold which so often lured the Spaniards to an evil fate. He sent out expeditions, one of which marched eight days to the northwest and reached the open prairies. It seems probable that De Soto approached the Missouri River, although he learned nothing of it.

At this very time, in the summer of 1541, De Soto and his starving followers must have been so near Coronado’s army that an Indian runner could have carried a message from one to the other in a few days. Indeed, Coronado heard of these white men and sent a messenger, who failed in his errand. Thus, in the first half of the sixteenth century two Spaniards, one starting from Tampa Bay in Florida and the other from the Gulf of California, practically completed a journey across the continent.9

De Soto’s wanderings on the west bank of the Mississippi are of interest here chiefly because he entered the Louisiana territory. He met with little save disaster, and after a bitter winter passed on a branch of the Mississippi., which seems to have been the Washita, he started southward with the remnants of his force. At the mouth of the Red River, on May 21, 1542, the baffled "conqueror" died. Surrounded as his survivors were by hostile Indians, they dared not leave his body in a grave lest the Indians should discover it; so this proud Spanish warrior found his last resting place beneath the waters of the Mississippi.

The survivors, led by Luis de Moscoço, at first undertook to go westward in the hope of reaching their countrymen in New Spain, and some chroniclers have credited them with so long a journey across the plains that they came within sight of the mountains. But their attempts to reach their friends in Mexico yielded no results, and they made their painful way back to the Mississippi. There they built boats and descended the river. They skirted the coast of Texas, and in September, 1543, the wretched remnants of De Soto’s once proud expedition reached Tampico.

Pineda had found the mouth of the Rio de Espiritu Santo, but De Soto is justly remembered as the true discoverer of the Mississippi. On this discovery was based an early claim to Louisiana. But the story of the Spaniards in North America was very different from their record in the south, where Cortes had gained an empire by his conquest of Mexico (1519-1521), and Pizarro another in Peru (1531-1534).. The early expeditions of the Spaniards within the present territory of the United States represented even larger possibilities, as they were the first comers in this new land.

Pineda, Coronado, De Soto, and other Spaniards made their journeys in the first half of the sixteenth century, and the oldest town in the United States, St. Augustine, Florida, was founded by the Spaniards in 1565. The Spaniards had sailed by the shores of Virginia long before Raleigh had dreamed of settlement.

It was not until 1605 that the French on the north founded Port Royal, now Annapolis, N. S., which was followed by Quebec in 1608. It was not until 1607 that the English founded Jamestown, in Virginia, and not until 1620 that the Pilgrims made their way to Plymouth. Thus in the struggle for a continent the Spaniards had all the advantages of priority, and they might have held North America. But Spanish discovery was not accompanied by the qualities which have wrought out a very different history for Anglo-Saxon expansion, and there were other obstacles.

Louisiana lay open to Spain in the sixteenth century, but the Spaniards, like other Europeans of their time, held to the "Bullion theory," — that the precious metals were the only form of wealth,—and the gold and silver of Mexico and South America blinded them to the opportunities awaiting them in the development of the Mississippi valley. Furthermore, after 1570 Spain’s energies were absorbed in attempts to suppress Protestantism in Europe and to crush the revolting Netherlands.10 In 1588 Spain’s maritime power was crippled by England’s destruction of the Invincible Armada.

All this checked a career in the New World which, continuing as it began, might have meant a warfare against heretics in Virginia and New England like that which stained the early annals of Florida. It might have meant also an assured grasp of the Mississippi and Louisiana. But Spain’s distraction and exhaustion gave a clear field for the English settlers on the eastern seaboard, and also for the French who came from the north to explore the Mississippi and claim the interior of our country.

The seventeenth century found Spain suspicious and uneasy, but for the most part inactive as regards Louisiana. In the early eighteenth century, about 1716, a Spanish expedition moved eastward from Santa Fé to check the French by establishing a military post in the upper Mississippi valley, but it came to a disastrous end. So far as the Louisiana territory is concerned the brilliant beginnings of Spain suffered an inglorious lapse. We owe to De Vaca, Coronado, and De Soto the amplest knowledge which the sixteenth century afforded of the interior of North America, but the Spanish desire for conquest and gold rather than real colonization and development proved impotent in the end.

Many years later than the Spaniards — not until the seventeenth century — came the French, adventurous, impelled by pride of country, desirous of territory and of trade, but like the Spaniards lacking the colonizing power of the race which finally dominated Louisiana.

6 A translation of this narrative follows Mr. George Parker Winship’s critical discussion of the Coronado expedition published in the Report of the Bureau of Ethnology for 1892—1893. "The Spanish Pioneers," by C. F. Lummis, offers a vivid sketch of early Spanish exploration and conquest throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Return to text.

7 See "The Spanish Pioneers," by C. F. Lummis.

Return to text.

8 There has been much historical discussion as to the discovery of the Mississippi, and the question of the claims of Pineda in 1519, of Cabeza de Vaca, who crossed one of its mouths in 1528, and of De Soto, has been argued at length by Rye in the Hakluyt Society’s "Discovery and Conquest of Florida," 1851. See Winsor's "Narrative and Critical History of America," Vol. II, pp. 289—292.

Return to text.

9 Winsor’s "Narrative and Critical History of America," Vol. II, p. 292.

Return to text.

10See "The Discovery of America," by John Fiske, particularly Chapter XII.

Return to text.

Chapter II.

Back to list

Back to Legacy

© 2001, Lynn Waterman