From the time of the "hunchbacked cows" of Cabeza de Vaca to the decade following the completion of the first transcontinental railroad, every traveler through the plains of Louisiana territory was impressed first by their extent, and next by the vast herds of buffalo. Then, they seemed countless. Now, the census of the handful preserved in the Yellowstone National Park and in private keeping can be taken all too readily. They were the mainstay of the flesh-eating Indians of the plains; but the slaughter by the Indians, barbarous as it was, counted as nothing beside that of the white hide-hunters and other merciless slayers — sometimes miscalled sportsmen. The completion of the Union Pacific Railroad divided the buffalo into the northern and southern herds, and ease of transit for hunters and the increasing pressure of newcomers hastened the work of extermination. The story of the buffalo forms a page melancholy but inevitable in the history of the West.

But the buffalo had their successors. The descendants of the Spaniards in Mexico owned cattle by the tens of thousands. Their cattle entered Texas, — sometimes by fair means, sometimes by foul,—and it was found that these sharp-horned, thin-limbed, muscular creatures throve on the buffalo grass of northern Texas. Seeing this, and eager for a market which did not exist in the distant Southwest, the owners drove the cattle northward. Even before the Civil War, Texas cattle were driven to Illinois. Soon after the war, experiments were made in driving cattle to Nevada, and even California was attempted. But the great route finally clearly marked out was almost directly north. It was found that the cattle gained weight in northern latitudes, and they were also brought nearer to a market. The opening of the first transcontinental road was an important factor. Thus the "Long Trail" was developed, as distinctive in its way as the trails worn by the pioneers, gold seekers, and emigrants.4 In 1871, over six hundred thousand cattle were driven across the Red River toward the north. Out of all this grew the era of the cowboy and his reign from Texas to Montana. The cattle towns where he held his court when free from the labors of the drive or range afforded another distinctive page in the history of the West. But at length there came the invasion of settlers and farmers, the private ownership of land and water rights, and the opposition of barbed-wire fences. The "Long Trail" was ended, and the cowboy5 of the days of wild herding has nearly passed away or is transformed into the milder herdsman of a more closely regulated industry.

The great trails of the West were worn by the feet of countless thousands for decades before the dream of a transcontinental railroad took practical shape. But the idea6 found vague expression as early as 1819, when Robert Mills, in his book on the internal improvements of Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina, argued for the connection of the Atlantic and Pacific by a steam road "from the head navigable waters of the noble rivers disemboguing into each ocean." Mills’s plan, however, as shown by his memorial to Congress in 1845, was for a road for steam carriages rather than for a railway.7

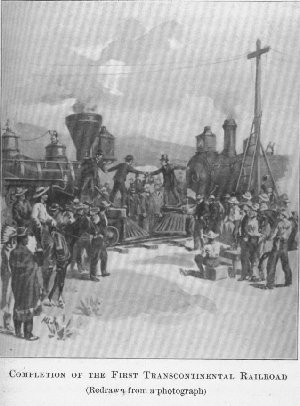

Of all the early advocates of a transcontinental railway the most enthusiastic and persistent was Asa Whitney, a New York merchant, whose life from 1840 to 1850, and much of his later time, was spent in urging upon Congress, upon capitalists, and the public, the necessity for surveys and the benefits to be derived from a railroad across the continent. But any practical result from the surveys undertaken in the fifties was delayed by the Civil War and by the hesitation of private capitalists, and yet the war itself made plain the need of a railroad to the western coast. It was not until 1864, after the government had doubled its land grant and increased its inducements, that ground was broken at Omaha for the first transcontinental railroad. In 1869 the Union Pacific advancing from the East met the Central Pacific coming from the West, and the last spike was driven at Promontory Point in Utah, completing the first iron highway across the continent.

|

(Redrawn from a photograph) |

The Union Pacific presented some typical features which have never been surpassed.8 in the abundance of Indians and buffalo on the plains, and of the thugs and thieves who invested Julesburg, Cheyenne, and other points with an evil reputation, the building of the Union Pacific held a certain preëminence. With this road began the work of the railroad surveyor and engineer in the true West, with its perils of all kinds on the plains and in the mountains, which forms in itself one of the epics of Western history.9

4 "The braiding of a hundred minor pathways, the Long Trail lay like a vast rope connecting the cattle country of the South with that of the North. Lying loose or coiling, it ran for more than two thousand miles. . . . It traversed in a fair line the vast land of Texas, curled over the Indian Nations, over Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana, and bent in wide overlapping circles as far west as Utah and Nevada; as far east as Missouri, Iowa and Illinois, and as far north as the British possessions." — Emerson Hough, in "The Story of the Cowboy."

Return to text.

5 "There, jaunty, erect, was the virile figure of a mounted man. He stood straight in the stirrups of his heavy saddle, but lightly and well poised. A coil of rope hung at his saddle bow. A loose belt swung a revolver low down upon his hip. A wide hat blew up and back a bit with the air of his traveling, and a deep kerchief fluttered at his neck. His arm, held lax and high, offered support to the slack reins so little needed in his riding. The small and sinewy steed beneath him was alert and vigorous as he. It was a figure vivid, keen, remarkable.

"The story of the West is a story of the time of heroes. Of all those who appear large upon the fading page of that day, none may claim greater stature than the chief figure of the cattle range. Cowboy, cattle man, cow-puncher, it matters not what name others have given him, he has remained — himself. From the half-tropic to the half-arctic country he has ridden, his type, his costume, his characteristics practically unchanged, one of the most dominant and self-sufficient figures in the history of the land. He never dreamed he was a hero, therefore perhaps he was one. He would scoff at monument or record, therefore perhaps he deserves them." —" The Story of the Cowboy."

Return to text.

6 Mr. J. P. Davis, in "The Union Pacific Railway," mentions an editorial in The Emigrant, a paper published in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as the first public expression of the idea. But this was not until 1832. Various other claims are recorded, including Senator Thomas H. Benton’s declaration at St. Louis in 1844 that men full grown at the time would live to see Asiatic commerce crossing the Rocky Mountains by rail.

Return to text.

7 Perhaps the reign of the automobile will yet show Mills a true prophet, though far in advance of his time.

Return to text.

8Some features of this life are sketched in "The Story of the Railroad." "The Union Pacific Railroad," by John P. Davis, and Mr. E. V. Smalley’s " History of the Northern Pacific Railroad," are useful for reference. A comparison of a map of the old trails and a recent map of the numerous transcontinental lines tells an interesting story.

Return to text.

9 Of this wonderful work of construction, Robert Louis Stevenson, in "Across the Plains," has given a vivid picture: "When I think how the railroad has been pushed through this watered wilderness and haunt of savage tribes; how, at each stage of the construction, roaring, impromptu cities full of gold and lust and death sprang up and then died away again, and are now but wayside stations in the desert; how in these uncouth places pigtailed pirates worked side by side with border ruffians and broken men from Europe, talking together in a mixed dialect, — mostly oaths, — gambling, drinking, quarreling, and murdering like wolves; how the plumed hereditary lord of all America heard in this last fastness the scream of the ‘Bad Medicine Wagon’ charioting his foes; and then when I go on to remember that all this epical turmoil was conducted by gentlemen in frock coats, and with a view to nothing more extraordinary than a fortune and a subsequent visit to Paris, it seems to me, I own, as if this railway were the one typical achievement of the age in which we live; as if it brought together into one plot all the ends of the world and all the degrees of social rank, and offered the busiest, the most extended, and the most varying subject for an enduring literary work. If it be romance, if it be heroism that we require, what was Troy town to this?"

Return to text.

Chapter 25

Back to Legacy

© 2001, Lynn Waterman