DISCOVERIES OF THE ANCIENTS

GEOLOGISTS class the ages of man as (1) the Palæolithic, (2) the Neolithic, (3) the Bronze, (4) the Iron. "Palæolithic" means "Old Stone", and refers to the time when man subsisted by hunting with weapons made from flaked flints and bone or horn. "Neolithic" means "New Stone", the age in which man found out how to cultivate the earth and to tame animals. After that came the Bronze Age, when men first smelted metals and made tools with cutting edges.

Now please do not imagine that these various ages are divisions of time, for they are nothing of the sort. As I have already pointed out, some races invented a great deal more rapidly than others. So all these four so-called ages may and actually have been in progress at one and the same time in different parts of the earth. For instance, the North American Indians were a Neolithic people when first discovered by Europeans, but the black fellows of Australia, who were not found until much later, were still in the Palæolithic state.

No one can so much as guess when or where man first smelted metal, but in any case it was a very long time ago. Very possibly the art was accidentally discovered. A hot fire built on a rock containing tin might have melted out some of the metal, and one of the tribal inventors would no doubt have noticed how the shining stuff hardened as it cooled.

Tin by itself is soft stuff, no good for making knives or spears, and copper by itself is not much use for any similar purpose, but when the two are melted together, forming what is termed an alloy, then this alloy, named bronze, is very much harder than either of the individual metals.

You will no doubt ask why bronze was invented before iron. The answer is simple. Both tin and copper melt at a much lower temperature than iron. Tin, indeed, will liquefy in an ordinary hot fire, but iron requires a far greater heat to melt it. It was not until men had become clever enough to use a bellows to increase the heat of a fire that they were able to use iron. So, although iron is a much commoner metal than either copper or tin, it was not discovered until a very long time after bronze came into use.

It is useless to try to guess how men first discovered that tin and copper mixed together made bronze, but we do know that bronze was in use at least five thousand years ago, and we have good reason to believe that the ancient folk who used it had secrets of their own for tempering or hardening it in a way which has been lost and never rediscovered. The modern man who made himself a razor of bronze would have a very poor time if he tried to shave with it, but the ancients made sickles, knives, swords, spears, saws, and razors out of this metal. Bronze was the metal used by the old Egyptians in all their wonderful works, and the Greeks, Etruscans, and early Romans were almost entirely dependent on bronze. We find quantities of bronze implements in ancient tombs and have discovered that the usual alloy was nine parts of copper to one of tin.

The invention of bronze was not made until man had given up his wild, wandering existence as a hunter and had settled down to till the ground, and to keep the wild animals—cattle, sheep, and horses—which he had tamed. It was a tremendous step forward, for until he had metal tools, man could not begin to build houses and cities, or to make all those thousand-and-one articles which depend upon metal for their manufacture.

While bronze was probably the first alloy to be made by man, the people of old knew of several other metals. In the Book of Numbers (chapter xxxi, verse 22), Moses speaks of gold, silver, brass (or bronze), iron, lead, and also "bedil", which is probably tin. But iron when first separated from its ore is comparatively soft, and it was no doubt a long time before some early inventor managed to alloy it with charcoal so as to form that much harder substance, steel.

The Egyptians were the great inventors of antiquity, and the beauty of the articles found in their tombs fills us to-day with surprise and admiration. A wonderful collection of these things may be seen in the British Museum.

The Egyptians were probably the first makers of glass. There are in the British Museum Egyptian glass vessels dating back to the year 2300 B.C., so that these are now forty-two centuries old. The story of the invention of glass, according to Pliny, a famous Roman writer, is that certain Phœnician merchants who had landed on a beach to cook their food happened to rest their pots on blocks of "natron" or soda taken from their vessel’s cargo, and found glass produced by the union under heat of the alkali and the sand. The historian Josephus attributes its discovery to the Jews, but others besides Pliny ascribe it to those wonderful traders the Phœnicians. At any rate, the art of glass-making spread throughout the ancient world, for we know that the Assyrians made glass, and that the Persians drank out of glass vessels. The people of India not only made glass but discovered how to color it and to produce imitations of precious stones. In the year A.D. 200 there were so many glass blowers in Rome that they had their own quarter of the city.

To return to the Egyptians, these people had also wonderful skill in tool-making. Some years ago the explorer Professor Flinders Petrie, digging in some ruins in Egypt, discovered a chest of tools of an Egyptian mason, probably thirty-two hundred years old. Among them he found a drill that was peculiar so that in drilling into granite a core was left. The drill was so made that when the workman had cut the hole as deep as required he could sever the core and lift it out. Professor Petrie not only found the drill, but three of the cores, and he asks, "Is there any drill made in Europe to-day that could do work like this?"

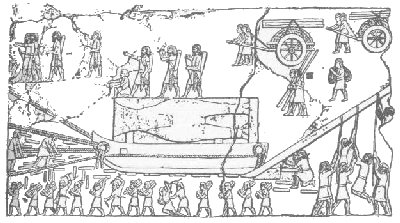

|

We have good evidence that for cutting hard stone the Egyptians used saws and hollow drills set with jewels, and these were worked under great pressure. We are, however, quite ignorant of how the jewels were fixed in the metal supports so as to stand the heavy strain upon them. Even with modern appliances it has always been difficult to fix diamonds in a saw or drill so firmly that there is little chance of their working loose. The Egyptians made babies’ feeding bottles out of baked clay, and not long ago there was found a bone collar stud just like those sold by hawkers in the streets, yet which was made long before Moses marched the Children of Israel out of Egypt.

The ancient Egyptians had doctors and surgeons. We have found probes, forceps, and other surgical instruments in their tombs. They were also good dentists. Jaw bones of mummies have been found with false teeth in them, and with teeth stopped with soft gold. In connection with false teeth, it is rather interesting that there is mention of these in early Roman laws. The first part of Number Ten of the "Laws of the Twelve Tables" forbids useless expense at funerals, but it is expressly stated that the gold fillings of the dead person’s teeth may be buried with the deceased.

The Egyptians had a preparation for preserving statues and stonework against the effects of weather, but the secret of this has passed with them. Again, they probably had magnifying glasses. That the magnifying glass is a very ancient invention we are certain, for some time ago the explorer Layard found in the ruins of Nimroud a magnifying lens of rock crystal which Sir David Brewster pronounced to be a true optical instrument.

The Egyptians must have possessed a pretty good knowledge of chemistry; they had the decimal system of numbers and an excellent system of weights and measures; while the way in which they and other ancient peoples transported enormous blocks of stone over great distances is certain proof that they knew much about engineering. They embalmed their dead kings so perfectly that the bodies are in splendid condition to-day. The secret of how they did this is lost, and so, too, is a great deal of the wonderful knowledge which they gathered during the thousands of years of their life in the rich valley of the Nile. Much of this knowledge was, no doubt, preserved in that marvellous library at Alexandria which at one time is said to have contained 490,000 volumes. The destruction of this library, begun in the time of Theodosius by a mob of religious fanatics and completed by the Arabs under Omar in the year 641, is by some people considered to have been one of the worst disasters which ever befell civilization. Others are, however, of the opinion that the destruction of these records opened the door to new ideas, new thought, and new inventions.

The ancient method of embalming bodies is only one of many secrets of old time which have been completely lost to the world and have not been rediscovered.

The Romans understood the principle of the lightning conductor. On the summit of the highest tower of the Castle of Duino on the Adriatic there was set from time immemorial a long rod of iron. A soldier was always stationed near it in stormy weather, and from time to time he put the metal point of his spear close to the iron. Whenever a spark passed between the rod and the spear he rang a bell to warn the fishermen.

The Chinese and Egyptians understood how to bore to great depths for water, and the Romans sank artesian wells; but exactly how they did the boring we do not know. Knowledge of these wells was lost for more than a thousand years. The oldest artesian well known in Europe was sunk in the year 1120 at Lillers in the French province of Artois, hence the name "Artesian."

The Greeks had a way of weaving linen or wool to form the pilema, a sort of cuirass which could not be penetrated by the sharpest of darts or arrows. This secret is lost—perhaps for ever. Malleable1 glass was made in the time of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. Neri, whose book on glass was published at Florence in 1612, speaks of this invention and says of it, "A thing afterward lost, and to this day wholly unknown, for if such a thing were now known, without a doubt it would be more esteemed for its beauty and incorruptibility than silver or gold, since from glass there ariseth neither smell nor taste or any other quality."

The art of making glass that would bend but not break was also practised in Persia. It is said that in the seventeenth century a French inventor rediscovered the art and presented to Cardinal Richelieu a bust made of malleable glass. He was rewarded for his ingenuity by imprisonment for life, lest the interests of the French glassworkers should be injured by the new invention.

This incident recalls to mind the unhappy history of the man who first discovered that very light metal, aluminium, of which we make such great use to-day. The Roman historian Pliny, who lived between AD. 23 and 79, relates how a certain worker in metals appeared at the palace, bringing to the Emperor Tiberius a cup composed of a brilliant white metal which shone like silver. While the artificer was presenting it he purposely dropped it on the marble floor of the chamber and bruised it so that it seemed injured beyond repair. But the workman took his hammer, and in the presence of the Court repaired the damage. The Emperor took the cup and noticed that it was far lighter than silver. He then questioned the man, who told him how he had extracted the metal from clay (no doubt that known to the modern scientist as alumina). Tiberius then asked if any one except the maker knew the secret, and the other proudly replied that it was known only to himself and Jupiter.

The Emperor turned to his guards and ordered them to take the inventor out and behead him instantly, and afterward to destroy the man’s workshops. The reason he gave for this brutal order was that if it were possible to obtain so wonderful a metal from clay the value of his own hoards of gold and silver would be reduced to nothing.

|

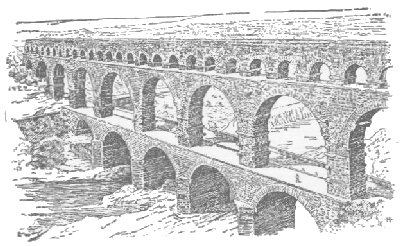

Yet in spite of this dreadful example the Romans invented many things. They had, for instance, a water supply brought from a great distance by nine wonderfully constructed aqueducts, three of which still supply the modern city; they had a system of drainage which was far ahead of anything that London possessed a hundred years ago. They had water mills for grinding wheat and other grain and for pressing olives. They even had sawmills. Water clocks for measuring time were introduced in the year 157 B.C. by Scipio Nasica.

We are aware that Rome under the Emperors had become a city of skyscrapers, or at any rate of houses many stories in height. Centuries elapsed before any other nation dreamed of constructing similarly lofty edifices. Roman architects even understood the principle of the lift, for excavations in Rome on the site of the Cæsars’ palace on the Palatine have proved that at least three large lifts were used to enable the Emperors to ascend from the Forum to the top of the Palatine.

So excellent was the Roman masonry that in many parts of Europe—in Portugal, for instance—walls of Roman bricks that were built more than fifteen centuries ago are still standing. Not only were the bricks excellently made and burned, but the cement and mortar, which are the weakest parts in a modern wall, were made according to recipes long since lost. In Roman and Greek buildings the mortar remains good even after the stones or bricks have crumbled with age.

Greeks and Romans both understood the manufacture of most beautiful and brilliant dyes, and they were able to make ink which was durable and lasting.

Other secrets of the ancients which we have lost are those of Damascus steel and Greek fire. Even modern Sheffield cannot produce sword blades such as were used by the Saracens centuries ago. The steel of which they were composed was so keen, hard, and tough that it could shear through chain armor. Of the exact nature of Greek fire we are ignorant. It was, however, a liquid composition which could not be extinguished by water or other ordinary means. The secret probably came to the Greeks from the East, and the fire was used with terrible results by the Byzantine Emperors.

The Western Roman Empire went to pieces in the year 476 and the whole Western world fell back into a state little better than barbarism. For centuries every one was fighting. Men were either soldiers, merchants, monks, or slaves; very few people could read, fewer still could write, and all the arts were neglected. The monks were the only people who had any education. Even theirs was not of a very high standard, and their superiors did not encourage them in invention or discovery; nevertheless practically all the work that was done for invention during the ten terrible centuries of that period stands to their credit.

During the Middle Ages Western man hardly climbed a single rung up the ladder of civilization. The inventions of the ancients were neglected or forgotten, and almost the only discoveries that were made were concerned with the art of war. The most important, that of gunpowder, is usually ascribed to Roger Bacon in the thirteenth century. But since some sort of explosive mixture of the kind was known long before his day and was actually used against the Crusaders in the form of rockets, it is probable that Bacon was merely the first person to make gunpowder in England. In any case, his mixture was so poor that it was of little practical use, and it was not until the year 1320 that the German monk Berthold Schwarz discovered a way of mixing the various ingredients so as to form a powerful explosive.

Seven years later, Edward III used rude cannon called "crackeys of war" against the Scots, and in 1346 he used similar weapons at the battle of Crécy. Yet for more than two centuries after that date all the powder used in England was imported from the Continent; it was not until the time of Queen Elizabeth that powder factories were established in Surrey at Long Ditton and Godstone.

Cannon, it will be seen, followed close upon gunpowder. The first were made of iron bars hooped together with iron rings; they were wider at the mouth than in the chamber; they fired stone balls, and were almost as dangerous to the users as to the enemy. James II of Scotland, for whom was built the great gun "Mons Meg", now preserved at Edinburgh Castle, was killed by the bursting of a similar piece called "the Lion." About the year 1401 cannon were cast in one piece of bronze, but it was

|

Of peaceful inventions of the early Middle Ages the most useful was that of spectacles. The earliest reference to spectacles is by an Arab writer of the eleventh century, and the famous Roger Bacon also speaks of them. Their invention is usually attributed to two Italian monks who lived during the thirteenth century. Early spectacles were very heavy and clumsy, and they were not much improved for nearly five hundred years.

|

I have spoken of water clocks made by the Romans, and no doubt you have heard about the device of King Alfred, who cut notches upon candles in order to mark the time.

The first clock of which we have any distinct record was made for the town of Magdeburg in Germany, about the year 996, by a monk named Gerbert, who afterward became Pope Sylvester II. This machine was worked by a weight. A century or so later, clocks began to be fairly common in the larger monasteries, but they were not much like our modern clocks. They were simply arrangements which rang a bell or struck a gong at regular intervals to call the monks to meals or prayers. They had no faces marked with the hours, nor hands.

It was not until the thirteenth century that we hear of clocks in England. In 1286 St. Paul’s Cathedral had a clock keeper. A little later, Westminster, Canterbury, and Exeter Cathedrals were the possessors of clocks. The oldest clock which is still in existence may be seen in the South Kensington Museum. It was made by Peter Lightfoot, a monk of Glastonbury Abbey. The great Abbey is now an ivy-clad ruin, but Peter’s clock, made five hundred years ago, is still in excellent order. The first clocks were huge and massive; portable clocks were first made early in the fourteenth century.

The Chinese assert that the mariner’s compass was invented by their Emperor Hoang Ti, in 2634 B.C. The Chinese claim that they were the originators of most of the great inventions is not fully accepted, but in this case there is no doubt that they understood the properties of a magnetized needle long before the Western peoples. By some it is supposed that the great Italian traveler Marco Polo brought the compass to Europe from China, but there is evidence that this instrument was rediscovered in Europe in the twelfth century. The Norse adventurers were the first to make practical use of this device, which is certainly much the most important of the inventions during the Middle Ages.

1Malleable, that which can be pressed into a different form without breaking.

Back to text.

Chapter 1

Chapter 3

Table of Contents

Return to Main Page

© 2000, 2001, 2002 by Lynn Waterman