History: 1923 Wood Co., Wisconsin's Indians

Poster: History Buffs

----Source: History of Wood County, Wisconsin compiled by George O. Jones, Norman S. McVean and others : illustrated. H. C. Cooper, Jr. & Co., 1923, CHAPTER II.

----1923 History of Wood Co., Wisconsin's Indians

THE INDIANS

The territory now included within the State of Wisconsin was the former home of various Indian tribes in regard to whose origin and history many speculations have been made and books written by historians and ethnologists, who, however, differ considerably from each other on some important points. This divergence of opinion is due to the difficulty of the subject. The Indians had no written language, and preserved their history-as much as they knew of it-through the untrustworthy medium of tradition. What has been since learned in regard to them depends upon the scanty records of the early missionary priests, who were more interested in converting them to Christianity than in ascertaining their origin or history, the notes of a few early travelers, explorers or fur traders, and the investigations of modern ethnologists, who, however, have to depend largely upon the records above mentioned.

About the middle of the eighteenth century the Sioux claimed and exercised jurisdiction over the country as far east as Lake Michigan and St. Mary; and they, together with the Chippewa, Winnebago, Sauk and Foxes and Menominee, appear to have been all the Indian tribes who inhabited or claimed the territory now within the state since white men came to the country who were of any note or became prominent by treaty stipulation. Of these the Chippewa, next to the Sioux, were the most prominent. The Hurons, Iowa, Illinois, Potawatomi, Kickapoos, Miamas and Ottawas appear to have had no permanent residence within the territory, but were for the most part but straggling adventurers passing through or temporarily ranging the country. Some Oneidas came from New York about 1826, and some Brothertown and Stockbridge Indians, also from New York, though originally of New England, came about 1822, and having bought a sort of half interest in lands of the Menomonees, settled chiefly in Calumet County. These two latter tribes were civilized and became citizens.

According to Thwaites, '"About 1820 the Chippewa occupied the northern third of the present Wisconsin, with about 600 hunters, whose trade was chiefly reached from Lake Superior by the Ontonagon, Montreal Bad and Bois Brule rivers. Such of the Sioux as were visited by Wisconsin traders from Prairie du Chien were located on the west bank of the Mississippi, and toward its source, but frequently ranged into Wisconsin as far as the falls of the Black, Red Cedar and St. Croix. The Sauk and Foxes were to be found for the most part in the lead district. The Menominee, with 400 hunters, were on the 'Fox and generally throughout northeastern Wisconsin, Black River being their western boundary, while the country of the Chippewa penned them in upon the north. Green Bay was their chief entrepot. Milwaukee was the most important rendezvous of the Potawatomi, who extended along the entire west coast of Lake Michigan and numbered 200 hunters. The Winnebago sought peltries around Lake Winnebago, up the Fox River to its sources, on the Wisconsin up to Steven's Point, about the head waters of Rock River, in the region of the Madison Lakes, and northeast to Black River, where they often overlapped the Menominee grounds; there were also a few of them on the Mississippi above the mouth of the Wisconsin." The Sacs (or Sauks), it is said, originated at Quebec, but about 1759 were driven by their enemies as far back as Montreal, and later to Mackinac and to the Sac River near Green Bay, where they were joined by the Foxes (or Outagamies). Their history is more or less confused and is marked by discrepancies between the different writers who mention them. Grignon, in his "Recollections," says that in 1746 they were driven by the French and their Indian allies from the Fox to the Wisconsin River, while according to Carver they were on the Wisconsin as early as 1736, and he himself found them on the Wisconsin in 1766, seven years after the fall of Quebec. In that year or the next most of them moved to Rock Island, as Black Hawk said that he was born there in 1767.

During the Civil War Indians were enrolled in considerable numbers in the Third, Seventh and Thirty-seventh Wisconsin regiments.

There are now about 1,300 Indians under the jurisdiction of the Indian agency in Wisconsin Rapids, and about 40 families of these are resident in Wood County. They live on land privately owned by them, acquired by homestead on public domain. The Indian act provided that the land to which the Indians ceded their rights could be homesteaded by Indians without fee. In regard to these Indians and their predecessors in Wood County and the vicinity, something more need be said, and it can be said no better than in the following article from the pen of Dr. Alphonse Gerend, of Milladore, who has devoted a number of years of patient investigation to the subject.

The Indians of Wood County. Wood County was a part of the territory claimed by various tribes of Wisconsin Indians. When the white settlement began the Chippewa were the most numerous. They had villages here and hunted, fished and traded in this region. The Winnebago had villages and camps along the Black River in the southwestern part and occasionally came up the Wisconsin River. The Menominee also laid claim to this territory. According to the statements of old settlers there were not many Menominee here.

The boundary between the Chippewa, M/enominee, and Winnebago was left undetermined at the Prairie du Chien Treaty of 1825 because all of theimportant chiefs of the Menominee were not present. At that treaty the Winnebago claimed the territory from the sources of the Black River to the Wisconsin, and the Menominee claimed the region west to the Black River. In 1827, at the treaty of Butte des .lortes, the boundary between the Chippewa and the Menominee was settled; the Chippewa were allowed territory as far south as Plover Portage. In 1831 several Menominee chiefs went to Washington and there the boundaries of their tribe were definitely fixed by a treaty. According to this treaty the boundary of the territory west of the Wisconsin was fixed from the mouth of the Soft Maple (Eau Pleine) River, up that river to its source; thence west to Plume River, which falls into the Chippewa; thence down Plume River to its mouth; thence down the Chippewa thirty miles; thence east to the forks of the Manoy (Lemonweir) River; thence down that river to its mouth.

There is no record to show that the Winnebago ever gave their assent to this definition of their boundary. They were forced to cede all of their lands east of the Mississippi by the treaty of Washington in 1837. Nevertheless many members of this tribe have continued to live in the Black River country from then until the present.

The first cession of this region was at the treaty of Cedar Point in 1836 with the Menominee. They ceded a strip three miles wide each side of the Wisconsin River from Point Bas to the Big Bull Falls (Wausau). Point Bas is in Section 10 of Township 21, Wood County. The lumbermen at once rushed into this territory, which was officially surveyed in 1839. The final cession was made at the Menominee Treaty of 1848, when that tribe gave up all its lands except a reservation. Of the early missionaries and explorers known to history, Father Menard was the nearest to Wood County. He was with the Huron Indians, who were refugees on the Black River, probably northwest of Wood County, from 1609 to 1662 (Wisconsin Magazine of History, June, 1921: "The First Missionary in Wisconsin," by Louise P. Kellogg). As early as 1828 Amable Grignon had a trading post on the Wisconsin River. The first post was in Adams County on Grignon's Creek; later he had another post on the west side of the river in Town 22, not far from Centralia.

Jean Baptiste Dubay had a post on the Wisconsin River. His trade was largely with the Chippewa. Prosper Beauchaine, the Wood County pioneer, now in his 103rd year, recently told the writer that he personally knew Grignon as well as Dubay. He states that Dubay and his son had a trading post for almost 40 years near the mouth of Mill Creek on the Wisconsin. He occasionally visited this trading post. He also was acquainted with a trader by the name of Samuel Germain, or Jermain.

The Potawatomi. With the exception of several families the Potawatomi have all left Wood County. During the latter half of the last century they were quite numerous in certain parts of this county. Not very many years ago Marshfield and its surrounding country, as well as Auburndale and Arpin were quite thickly inhabited by these Indians. For years after the first white settlers arrived they still outnumbered the whites in these localities.

These Indians, former members of the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians, formerly occupied the west shore of Lake Michigan. At the great Chicago Treaty of 1833 they ceded this territory to the United States. Thereupon most of the Chicago and Milwaukee Indians were removed by the government to territory across the Mississippi River into Iowa. Later they were given land in Kansas. The Potawatomi north of Milwaukee were not removed to Kansas and although some went there of their own accord the most of these again returned to their former villages. Others went to Canada and Michigan. Of these some also again returned. However, through the influx of white settlers they were soon crowded out of their hunting grounds and villages near Lake Michigan and gradually drifted northward. Some moved from village to village, remaining one or several years at each place. From Chicago or nearby some went to Milwaukee, and from there to Waukesha, Theresa, and the Horicon Marsh. Some also moved to Indian villages in Fond du Lac, Sheboygan, Manitowoc, and Calumet Counties. The occupants of these villages finally drifted to Waupaca County on or near the Little Wolf River, where there were some large villages. Here they remained ten years or more, when some again moved farther north, and others came to Mosinee and Wausau and to the sites in Wood County and beyond. Many of the Potawatomi from Kansas, preferring the hills and forest of Wisconsin to the prairie, also again returned to Wisconsin, to Wood County especially. The Wood County bands thus were composed of Wisconsin Potawatomi who had received no land in Kansas, and returned Kansas Potawatomi. Wood County was inhabited by bands of Potawatomi during the entire latter half of the last century. After John Young and his band left in 1899 or thereabouts, there still remained quite a number of families around Skunk Hill and near Grand Rapids. During the last twenty years most of these have left for Forest County and others for Kansas and other points.

Congress recently allowed the claims of the Wisconsin Potawatomi to their share of annuity monies (even though they did not remain in Kansas) for buying land and building homes. Consequently most of the Wisconsin Potawatomi families who live mainly in Forest County at present now occupy new frame houses and own land received from the government. Forty acres were allowed each head or member at the time of the allotment. At present there are 300 Wisconsin Potawatomi and 42 Kansas or Prairie Band Potawatomi in Wisconsin. The latter have rentals from their lands in Kansas. There are 3,700 Potawatomi in the United States and 3,000 in Canada.

Village Sites. The writer will attempt to describe the various Indian village sites in Wood County. A few of the sites situated in Marathon County near the border will be included, as they were occupied mostly by former Wood County Indians. Most of these sites are situated along and near the various rivers and creeks and will be described according to their location.

Sites Near the Little and Big Eau Pleine Rivers. The village on the Saunders place was one of the largest in this vicinity. It was located in Auburndale Township, in the northeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 6 and the northwest quarter of the northwest quarter of Section 5, extending across the county line to the Saunders place in Section 31 and 32 in Day Township, Marathon County. This site was occupied for many years prior to 1875. This large village held 400 Indians winter and summer. There was a clearing or clearings of about 60 acres extent. Some of the large tree stumps were still standing in the principal clearing, and others lying on the ground. A large burial ground was located there. Many of the graves were afterwards disturbed by the plow and their contents exposed. Some coins and a soldier's medal were found here.

When Mr. Otto Saunders purchased this land about 40 years ago, he paid the Indians $200 for their clearing to get rid of them. They had no legal title to the land. After receiving and spending the money, a part of them still refused to move and Saunders family set fire to the wigwams, and even then one old squaw refused to leave and was hauled out of her burning hut. From this place the village moved to a point on the Little Eau Pleine River southeast of Rozellville. John Young was the chief of these Indians. According to the description of many people, who knew him well, he must have been a man of refinement and considerable education. He could read and write well and according to Mr. Jacob Frieders, living at the former location of "Indian Farm," could talk some German.

He was the leader and best known Indian in this vicinity, and with the possible exception of Chief Kee-ah probably had more influence and authority than any other Indian. A daughter and other relatives of John Young are still living at the Potawatomi village at McCord, Wis. There are several granddaughters in Wood County. Mrs. James White Pigeon and Mrs. Ed Wilson both being daughters of Mrs. Ketch-ka-me, of McCord, daughter of John Young. They reflect in a general way the qualities of their ancestor. According to Albert Thunder, John Young was born in Illinois. When nine years old his parents moved to Wisconsin. First they settled on the East Fork of Black River, near New Dam; from there they moved to Powers Bluff (Skunk Hill), and later to the villages on the Little and Big Eau Pleine. John Young was almost 70 years old when the Indians left the Big Eau Pleine. He is buried at McCord. Another well-known figure among these Indians was old Indian Louis, familiarly known as Uncle Louis. Mr. Mich. Krings of Auburndale met Louis at Theresa over 60 years ago for the first time, met him again at Kiel, Manitowoc County, 53 years ago, at Rockville 48 years ago, and at Bear Creek, Wood County, 34 years ago. According to his own statement Uncle Louis' age then was 107 winters. Indian Louis is still remembered in the city and county of Sheboygan, as well as in Manitowoc County, and other places.

The Noons, in Indian Noque, of which there were four, John, Jim, Will; and Louis, are still well remembered. They often worked for the early settlers, peeling bark from elm trees. Chief Albert, probably a Chippewa, Joe Elk, and Sam Sky are other names mentioned in these reminiscences. These Indians did considerable trading with Mr. R. Connor, who had a store at Auburndale.

The ''Indian Farm." The first occupancy by the Potawatomi of the site known to the whites as Indian Farm probably does not date back as far as the previous one. It was, however, occupied by them many years prior to 1890. The Chippewa lived in this vicinity ever since the whites came to Wisconsin. This village was located about four miles northwest of Rozellville, a quarter of a mile south of the Big Eau Pleine, in the north half of the northwest quarter of Section 1 and the northeast quarter of Section 2, and extended into the adjoining sections of Cleveland Township. Here was an irregular clearing about 40 or more acres in extent. It appears as if each family, or in some instances several families in common, had made a separate clearing. The wigwams were placed either separately or as one of a group in small open spots in the woods. Their gardens were near the wigwams. They raised potatoes, beans, corn, squash, and onions. The corn after being dried and shelled was placed in a "mokock" and hung up in the wigwam. For use in baking corn cakes it was pounded in a mortar or ground in coffee mills. The squaws baked almost daily. After their work was finished they would squat down on the floor and enjoy their pipes or chew tobacco. Five-year old children occasionally did the same. Muskrat, fresh or smoke dried, constituted the chief meat food. Squashes were cut up in thin slices, dried, and stored for winter use. This was then cooked and mixed with wild rice. In the summer they would pick berries. Blueberries and cranberries were often sold. A white settler states that at one time when they returned from Dancy, where they had been picking blackberries, he bought a washtub full (50 quarts) from them for one dollar and a half. Deer hunting was a very common occupation, and it is said bells were often used for this purpose. Often a stalwart Indian could be seen carrying a deer on his shoulders. Occasionally the squaws carried in the game. The wigwams were oblong, square, and round in shape. Some were constructed of bark, others were covered with mats made of bullrushes or reeds and a few others with bear and deer skins and some with brush. John Young, the chief, occupied a log cabin. Here also was a largle cemetery, and a dance circle with smooth and well leveled floor, enclosed by a railing and board seats.

|

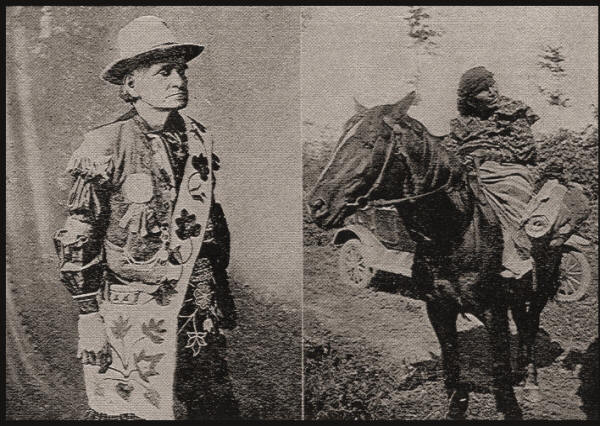

John Young |

Potawatomi Woman |

There were at certain times from thirty to fifty or more families living here. During their dances and feasts there often were Chippewa visitors, and occasionally some from other tribes. John Young, it is said, had a ceremonial pipe with a quarter-pound capacity, that would be smoked on these occasions. In spring they often had a sugar dance, when 400 to 500 Indians would gather for a week's pow-wow. An instance is mentioned showing the authority of John Young in this village. One of the Indians, Little Joe by name, still living near McCord, became unruly. John Young ted him by his hands to a tree, and there he was obliged to remain for the rest of the day.

These Indians had many dogs and ponies. Most of the ponies were tame, but some were quite wild and would occasionally jump over a brush fence. Frequently when they moved camp a long train of ponies loaded down with bark mats, skins, and blankets could be seen following the trail into the thick woods. A buck, or several, holding a gun in his arms, rode ahead and the other ponies followed him. The squaws with children were usually mounted and some of the men walked beside the ponies. Sometimes the men rode and the squaws walked. Often they could be seen taking slippery-elm bark to the trading house. The bark was carried in bundles hanging across the backs of the ponies. This bark, of which they gathered large quantities, was taken sometimes as far as Colby, Medford, and Dancy, there being trails to all these places. It was stripped off the trees in spring, after which it was dried, rolled, and tied up in bundles. Over a radius of many miles these trees were denuded and many dead red elm trees could in consequence be seen standing or fallen on the ground. When some of the early settlers arrived most of these trees had already been stripped for miles around.

The late Mr. John Brinkman of Rozellville traded with these Indians for many years. He came here about 1880. He could talk their own language. These Indians trapped and bartered chiefly the skins of muskrats, skunks, foxes, raccoons and sometimes weasels, otters and minks. They also gathered ginseng and made maple sugar which they also occasionally sold. Mr. Brinkman during one season bought almost $3,000 worth of ginseng root, paying the Indians at the rate of $2.00 per pound. The Indians also gathered evergreens and occasionally brought in deer hair which were bought and shipped by the traders. Venison, i. e. the hams then known as "saddles" were also bought and shipped. They tanned deer skins and made moccasins, mittens, tobacco pouches, jackets, and leggins. Each Indian had one or several pairs of large snowshoes. Baskets of all kinds and sizes were made. Red with blue stripes was a favorite color for their blankets. In the earlier years they wore shirts which they made from calico, breech clouts and also buckskin jackets, leggins and moccasins, and when hunting a powder horn or cartridge belt with a knife and scabbard completed the accoutrement. Occasionally one or more Indians could be seen at Brinkman's or at Marshfield in full regalia, wearing feather head-dress, sashes, moccasins, etc.

The following are the names of some of the Potawatomi of this village, some of the younger of whom are still living at the village in the forest near McCord: Jim Spoon, Tom, brother of John Young, Frank Young, Jim Young, Big Nose Joe, Sam Brown, Tom Enowa, Jack and Norwegian Saginaw, Jim Agen, Joe Nequeskum, Nwee or John Louis, Joe Nodogee, Shug-na-abo-go-quah, and Tu-kum. The latter, known as Old Tukum, died at Brinkman's place the morning he returned from Kansas. Joe Nequeskum died some years ago near Phlox; it is said that he was a son of the well-known Potawatomi chief Wampum, or Wamexico, at Manitowoc. One old Indian from this village was from Chicago and stated that he sold furs to early traders there. Another one of these old men went by the name of Captain Jack. Mr. William Geblein, who located in Marathon County fifty years ago, states that some of these Potawatomi who lived here at the time of his arrival, at one time had their homes at Theresa, Wis., where he had known some of them. There was an Indian village at Theresa on the Rock River, where the "Soo" depot is now located. Solomon Juneau was looked upon as one of their chiefs.

About 1880 many of these Indians left the "Indian Farm" and moved to Perkinstown, Taylor County, Wis. Many again returned to Skunk Hill and this place later. They left here permanently twenty-two years ago for Perkinstown, thence to McCord and points in Forest County and other places. Prof. H. C. Fish, a former teacher in the Marshfield High School, writes: "In the recollection of our first citizens the 'Indian Farm' was a rendezvous for all Indians. The Potawatomi village lay in a sequestered nook on the hill. On this site is a large burying ground, and only a few years ago when the farmer was doing his spring plowing the horses would once in a while step through into a grave. Mr. Hanson found a dozen cache or store houses on his place. At the foot of a gentle slope near the principal clearing is a large bubbling spring with its many divergent paths tramped smooth by the moccasined men, each narrow path leading to some old home in the woods. One cache pit on this farm was 42 inches square and three feet deep, lined with small poles and earth heaped up around it so that it seemed as if it was built in a mound. From that site a trail extends along the top of the hill to the Chippewa village one mile east and the second part of the old Indian Farm. This trail had been used in later years for a logging road, yet the deep path trod by many a silent-footed red man is plainly visible. The Chippewa village and burying ground lay on the hillside overlooking the Big Eau Pleine and a broad expanse of wilderness. The trail from the Chippewa site extends down the river a mile, crosses the Big Eau Pleine to the northeast, and then on to Mosinee. The third trail in this section started a mile north of Rozellville and went due north two miles, east three miles through a wild country, crossing the Big Eau Pleine at that most picturesque place, the old Indian ford; it then zigzagged northeast three miles and then east into Mosinee." Some of these Chippewas by name were Paul and Pete Whitefish, Joe Alex, Joe Shubka, John Skimes, and Jack Dout. Prof. Fish obtained the following facts from old settlers pertaining to a custom of the Indians in killing their aged. "In 1872 there was an old squaw who lived out near Rozellville.

She was well known around that country. As time went on she became more and more useless and at last could care for herself no longer. The Indians had a council and decided they must shoot her. So they gave her three days respite. During those three days she blackened her face with gun powder and chanted the death dirge; then she disappeared. For a long time no one knew anything about her, but at last it crept out that the Indians had shot her." "The second example happened in 1876. Old man Saginaw was blind and quite a care for his sons. He had clung on to life with remarkable vitality and it seemed as if he would outlive the rest of the family. One day he was in town with one of his boys and when they had started for home his son tried to kill him near the present site of the Thomas House, but he was prevented by our early townsman Louie Rivers. Time went on. The boys and the old man had always lived out between the Big and Little Eau Pleine near Week's mill. One day Thomas Saginaw returned from hunting and said to Jack and the other boys, 'Why do you keep talking about killing the old man and never kill him?' At that he turned and shot the old man dead. Jack Saginaw is buried in Section 36, Township 27, Range 4 East, near the picturesque Indian ford."

Riverside Village Site.-Another favorite haunt of the Indian was at Riverside. The older settlers still remember the dances held here. This site was in Sections 23 and 24 of McMillan Township.

Lutz Village Site.-Another old village was on the Lutz farm, in the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter of Section 30, Day Township.

Fish Dam.-On the Engman place was a V-shaped fish dam made of stones. There also was an Indian ford in this neighborhood.

Other sites were in the southwest quarter of the northwest quarter of Section 26 of Day Township and in the southeast quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 34 of Day Township.

Lahr Burials. There was a burial place on the old Lahr farm in the southeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 25, Day Township.

Austin Village Site. There was a Chippewa village and cemetery on the old Austin place. This was situated on a hill overlooking the Big Eau Pleine River, in the northwest quarter of the northwest quarter of Section 6 of Green Valley Township.

Berdan Camp. A small camp was situated on the George Berdan farm in Auburndale Township, in the southeast quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 10. When the Berdan family settled here in 1876 there was a cluster of wigwams here near a fine spring. Mr. W. Berdan, now residing at Milladore, relates that when a boy he was lost in the woods. An Indian found him and took him to his home.

Rice Lake Sites. Rice Lake and the village sites-prehistoric and historic -along its border, constitute one of the most interesting regions in this vicinity. Messrs. G. H. Reynolds and H. C. Fish, former residents of Marshfield, in 1906 followed the old Indian trails and described many village sites and mound groups for the Wisconsin Archaeological Society. Mr. Peter Hoffman, who formerly owned a farm on Rice Lake, gathered an interesting collection of prehistoric Indian stone artifacts here. This collection may still be in existence in Marshfield, where Mr. Hoffman located after selling his farm to Mr. G. H. Reynolds. Rice Lake before it was drained formed a large bayou of the Little Eau Pleine. It was filled with clear water fed by springs. Wild rice was very abundant along its shores. Fish and fowl were plentiful. Around the lake was a heavily timbered country chosen by the Indians as their camping and battle grounds. This extinct lake is situated in the southwest portion of Green Valley Township. Smoky Hill.-The following interesting article was taken from a newspaper clipping. The writer thus far has been unable to ascertain the name of the paper. "Smoky Hill rises up to the southwest of the lake and from the bank overlooking the lake and from the mounds and other evidences, was the Chicago of the Wisconsin River valley. The Indian tradition tells us that after many wars the place became haunted and on certain times of the year a great smoke would rise from the tree tops, but nothing ever burned. It was for this reason that it derived its name. When Chief John Young and his tribe rendezvoused near Rozellville, he ofter related the story of Smoky Hill as told him by his forefathers. It was no doubt a superstition but it is said that the Indians would never trespass there, believing in their untutored minds that it was possessed by the spirit of a murdered chieftain, whose anger even after death manifested itself in clouds of smoke as a warning to keep away."

"It was left to Peter Chaurette to hand down an event of importance which took place on this hill. Peter Chaurette died June 29, 1884, at the age of 74, and lies out in the Rozellville cemetery, forgotten except when brought to the minds of our old timers. He was a one-armed half-breed who had lost that member, Mr. Rozell says, in a hunting trip. Mr. Chaurette was educated in Montreal. His father was a French soldier and knew of the battle on Smoky Hill, and this was handed on down to his son and thence to many of the older settlers. "In spring, 28 years before our Declaration of Independence was signed, the Chippewa left their camping grounds on Smoky Hill and went down the river for sugaring or to take their furs to some trading post. It was not long before runners came up with the main body of the Chippewa and told them the Winnebago had taken possession of their village on Smoky Hill. From the natural position of the hill with its surrounding swamps and impregnable forest, the Chippewa knew that they could not take it without aid. A messenger was sent to Green Bay asking for ten soldiers to drive the hated Winnebago, or as the French called them, the "Puants" or Stinkards, from this region teeming with game of the forest and lake and rich in fields of rice. The French sent them ten or twelve soldiers, each armed with a gun, and the fort also sent a few guns for the Indians. They had for additional equipment two two-inch field pieces. During the fall the warrior crowd started from the falls where Wausau is located, and paddling speedily down the Wisconsin River the band turned into the Big Eau Pleine River. The trip up the river was swift and secret. When they reached what was later Weeks Mill in Section 13, Township 26, Range 5 East, they were one and one-fourth miles from the Little Eau Pleine. They portaged across this place and landed three miles below the place of conflict. One battery went down the river to cut off any bands of Winnebago who might be waiting in ambush for the Chippewa. The other battery quickly, in the night, steered for the hill of smoke. They reached the place and found it strongly guarded.

With their superstitious fear of fighting in the dark, they lay low until the birds whispered to them of an approaching day. The Winnebago were on guard and at once the tragedy of the hill was on-300 Chippewa with their 10 or 12 Frenchmen matched against 300 Winnebago. It was no easy matter for the Chippewa to skulk through the surrounding swamps, nor for the French to get near the defending force on the slope. With the better arms of the French, for a time the Winnebago were driven slowly back, and many a redskin fell toward the French as the little two-inch spurted out its fire and smoke. But the powder soon gave out and the battle raged with a listless fire of guns, the bow and arrow, the spear, and the tomahawk. All that day the fighting was kept up with varying success until at last by the superior cunning of the French and Chippewa the Winnebago fell back and fled east through forest and swamp, and gathered their forces together some seven miles down the river near Section 33, Township 26, Range 6. Here to their fearful surprise they met the first battery. The last stand was made as a wolf fights for life. The desperation of the conquered can no longer be measured by muscle, but with the thought of what capture meant to them-torture over fires-they sprang to the center of death. Flight had weakened them, their arrows were almost gone. With a short struggle all was over. The Chippewa again went back to the spot surrounded by all that was beautiful; the French to their trapping and to the fort, telling of this occurrence as one of the many tragedies that made life for them one long source of interest. We do not know how long the Chippewa remained here, but today the Indians of all tribes look upon this hill with superstition and grunt a few inarticulate words about a Big One that dwells there."

Smoky Hill Mounds.-There formerly was a group of conical and oblong shaped mounds on this hill. The conical or circular mounds were from forty to sixty feet in diameter. There were formerly large tree stumps on some of these mounds. Messrs. G. H. Reynolds and H. C. Fish explored several of these mounds. In one, two skeletons were found, one of which was in a flexed or sitting posture facing east. Charcoal, ashes, and a few potsherds were also found. In another mound only a skeleton was found. This former island, "Smoky Hill," is 6b acres in extent. Mr. Charles Brinkman, who has lived on the hill for over 20 years, stated to the writer that formerly the Indians would occasionally come to the hill to trap. However, they would not remain on the island after dark, but row across to the north bank of Rice Lake and camp there over night. The superstitious fear of encountering the "White Deer" and "Hairy Man or Monster." Hoboglins that haunt the hill caused them to make their departure before darkness set in.

The Portage.-Another very interesting and historic spot is three miles down the river at the portage where the Big and Little Eau Pleine are but a mile and a quarter apart. On the north bank of the Little Eau Pleine, on the Straub farm, three conical and circular mounds can still be seen in the cultivated field. Some of these mounds were dug into. In one mound two skeletons were found. In another, it was said, there were four feet of human bones, some stone arrow heads, and pottery. In the third no evidences of burial were found. There was a ford across the Little Eau Pleine at this point. South of the Eau Pleine is a small "island" surrounded on all sides by marsh and in former years entirely by water. This island is situated about one-half mile south and one-half mile east of the group of mounds just described. On it are three small mounds. Two of these are of a conical shape, one is oblong. Between these two rivers, was a well defined trail. At the north end of the portage, south of the Big Eau Pleine on the W. C. Goes farm was the site of a Potawatomi village. Here was a cemetery of fourteen graves. It is said that a well-known chief lies buried here. On the Fred Baur place some old coins and stone relics were found. Bear Creek Sites.-Along the course of Bear Creek were a number of village and camp sites. Residents of the township of Milladore remember one camp especially. This was situated in Section 16, about one mile south of Bear Creek on a well chosen sheltered spot. There were some pines here six or seven feet in diameter. The stretch between the Little Eau Pleine Swamp and Mill Creek was covered by some of the finest pine forest in Wisconsin. There was a clearing of about two acres in extent, on which were several log cabins and tepees covered with skins of bear and deer and reed mats. A war dance was enacted here occasionally, compared to which the pow-wow dances of today are very tame affairs. The long braided hair of the Indian women was often a source of admiration to the white visitors. There were about 50 Indians in this village winter and summer.

Mill Creek Sites.-Mill Creek was another favorite haunt of the Indians. On the H. Bertram place in Section 13 of Sherry Township there was a clearing and a cemetery composed of six graves. Some years ago a bark wigwam was still standing here. For years after the Indians had left this place they returned in the fall while gathering ginseng and visited these graves. When these graves were plowed over skeletons were exposed. These had been buried in pine wood boxes. Small elevations until recently marked some of the graves. Others were covered with boulders. Coins, bangles or ear rings made of coins, porcelain pipes, traps, etc. were found.

Kee-Ah's Village.-On the former Fred Graham farm on the west half of the southeast quarter of Section 3, Arpin Township, on Mill Creek between Auburndale and Arpin, was one of the largest villages in Wood County. This was sometimes referred to as Kee-Ah's Village. Kee-ah was the chief of all the Potawatomi in this vicinity. It is said' that he has descendants at Stone Lake, Forest County. He is probably buried at McCord, Wis. Skunk Hill.-The bluff known as Powers Bluff was known to the Indians as Tah-qua-kik, or Tah-quaw-king. It is said that some Potawatomi already lived at Skunk Hill in 1866. Skunk Hill, as Powers Bluff is commonly referred to, may not at present be called an Indian village in a strict sense of the term, as there are but several Indian families still living on the hill at all seasons of the year. However, during the time that the ceremonial dances are held, this well known hill takes on the aspect of a real Indian village. During the first days of May, just before planting time when the "oak leaves are about half their size," the first big dance is held on the hill. Then the Indian again returns to his former hearths and amid the chanting and the beating of drums gives thanks to his God for the return of spring. Indian guests and visitors come from distant parts of the state. Former residents of this and other sites of Wood County come from the Potawatomi village at McCord, Flambeau, Stone Lake in Forest County, and from Laona and Wabeno. Visitors frequently come from Kansas, Michigan, and other states. The Winnebago of Wood County regularly attend these Potawatomi ceremonial dances. Again, about the first days of July, when the ferns among the rocks and the flowers on the hill are at their loveliest, this sleepy hill becomes imbued with life as the Indians again resort hither for the performance of their sacred rites. Some come by train and alight at Arpin, the nearest station. A few come by automobile, while some may come by team all the way from McCord and Laona. One old squaw already past the seventieth milestone of life, "Annabelle Good Village" by name, can be seen trudging along the country road, leading her grandson by the hand and heavily burdened with bags and baskets, gradually wending her way towards the hill. This dance the Indians call their religion dance or dance of thanksgiving. A lack of space prevents the writer from describing it further than to state that it lasts four days.

| Above: The War Bundle Sacrifice | Below: Bark House of Skunk Hill Indians |

It is conducted in the dance circle. There are five drums and eight drummers, the latter going from one drum to another until all drums have been in use. Eagle Pigeon, who wears an eagle feather in his hat, is one of the leaders. The old men, White Pigeon, John Mustache, John Nouvee, Jim Young, and a few others, are the speakers. After each interval one of these gives a brief address. The Link boys, Bill and James, are masters of ceremony at the dance. The women at certain times join in the chant but do not dance. There is some variation in the ceremony from day to day. The last or fourth day seems to be the most important. Great earnestness prevails at all times. The Indians all appear in their best clothes and fineries, and some in full regalia, with faces painted with red stripes, etc. Some carry wands and others war clubs. The last day the eagle feather war bustle plays a prominent part in the ceremony. White visitors are permitted as spectators, but taking pictures of the dance is strictly prohibited. At the close of the fourth day at about 5 p. m. the drumming ceases, the four flags are taken from the poles, and the Indians march around the circle to their lodges and cabins, and the dance is over.

Another religious dance which shares with the foregoing in importance is the Medicine Lodge dance. This dance is the great religion dance of all the Algonkin tribes. According to the origin myth the medicine dance was given to the first man by the gods below to make up for the loss of his brother or companion whom they had enticed away from him. This dance is held whenever a new member is initiated into the medicine lodge society, or else to ask for the recovery of an afflicted person, or for other similar purposes.

After the dance some of the visitors from the distant parts of the state usually remain on the hill for a time before making their departure. A "Peace Dinner" is often given before the guests leave. Later during the summer, or towards fall, there is a harvest dance.

Among some of the well known Indians on the hill was the Indian, Chicog, from the Flambeau reservation. According to some Potawatomi Indians, the city of Chicago received its name from one of Chicog's ancestors, a chief by the name of Chicog. The mention of Chicago first appears in narratives describing LaSalle's expedition; so if there should be any basis for the Indians' claims as to the origin of the name, the tradition must have been brought down hundreds of years. At any rate Chicog was an interesting young Indian. The writer has a picture of him and his two sisters, taken at Flambeau. Young Chicog, as the writer was informed, died at Battle Creek, Mich., while serving in the army during the late war. His sisters are probably still living at Flambeau.

The writer has been able to obtain some very interesting material and pictures of old Potawatomi Indians and chiefs as well as a collection, at present exhibited at Madison, of most interesting Potawatomi relics. He is much indebted to Dr. A. S. Pflum of Milladore for kind assistance in this work. Before leaving this subject the writer would call attention to a jut of rock standing out prominently from the crest on top of the hill. This rock is known as "Spirit's Chair" according to a legend woven about it. The cemetery on the hill is quite large. The graves are covered with "roofs" constructed of slabs, boulders or small logs thickly covered with moss. Some well-known chiefs are buried here. Many a noted hunter, warrior, or chief, many an Indian whose name is appended to some important treaty, lies buried in one or another of the many Indian cemeteries of Wood County and this vicinity. Simon Kahquados, a chief of the Forest County Potawatomi, states that Che-chaw-kose is buried at Skunk Hill. Che-chaw-kose is mentioned in the treaty of Oct. 27, 1832, made at Tippecanoe River. According to Simon Kahquados he was a brother of the chief, Ah-quee-we, of Sheboygan, a signer of the Chicago Treaty of 1833. The writer has a British medal and other relics of Chief Ah-quee-wee, as well as a British medal (George III) and an old United States flag, and other relics, formerly belonging to CIhief Wampum of Manitowoc, another signer of various treaties. A Potawatomi Indian, who ten years ago still lived near Wisconsin Rapids, but who moved with his family to Stone Lake, Forest County, is the proud owner of a Washington medal. This was given to his grandfather, who was a chief at or near Chicago.

At present John Nouwe, Mrs. Rose Dekorah, and Eagle Pigeon, the oldest son of White Pigeon, with his family, are the only permanent residents on the hill. Albert Thunder, White Pigeon's son-in-law, lives towards the south at the base of the hill.

John Nouwe, also known as John Louis, is over 80 years of age. He was born, according to his statement, on the Lake Michigan shore between Milwaukee and Chicago. He still remembers all the various Potawatomi villages near Milwaukee, Waukesha, Horicon Marsh, Sheboygan, Manitowoc, and Waupaca counties. He mentions a certain river by the Indian name Men-neu-keh Sebe. This the writer has not yet been able to locate. When asked the meaning of the term Sheboygan in Indian, "Shab-wa-wa-gon," John Nouwe without much thought gave the meaning as: "A noise that goes through you which was heard at the mouth of the Sheboygan River." John Nouwee's mother died in Kansas and his father about one mile east of Steven's Point. He is a widower and has one daughter living in Kansas. White Pigeon, probably the best known of these Indians at present living in Wood County, is not a Potawatomi but a Winnebago; his mother was a half Potawatomi. White Pigeon married a Prairie Band Potawatomi woman and lived with the Potawatomi so long that he was cancelled from the Winnebago roll and enrolled as a Prairie Band Potawatomi. His parents went from La Crosse to Kansas, where he was born. He came to Arpin in 1907. The Indian name for White Pigeon is Wab-me-me. White Pigeon occasionally tells of the days when he hunted Buffalo on the plains. The following article entitled "The Indian's Feelings On the Land Problem," is another of the very interesting articles that appeared in one of the Marshfield papers in 1905-1906. The writer has not been able to ascertain the name of the paper or the writer of the article.

"One of the Potawatomies who had lived a long time on his government farm in Kansas came back last summer to good old Wisconsin and was sitting under the porch of his little log hut dreaming of former years here. After a long time in thought he looked up and said, 'Kansas so smooth. No like it.' Then his face lighted up, 'Wisconsin a good place.'

"When we look over this district which includes Wood, Marathon and part of Clark County we can say emphatically that Wisconsin was certainly a good place for the silent man of the forest. Here they had the beautiful, shady, stream-cut valleys, the hills covered with hard maple, ridges of hard wood and forests of pine. The marshes gave to them grasses and reeds for their baskets and mats and filled their crude kettles with many a wild fowl. Then each fall the wild cranberry was a source of profit to them. The lakes and rivers yielded their wild rice and fish and cargoes of beaver, fox, mink and rat were trapped along the banks. The small cleared space around the log hut, fertile as the Nile, gave an abundant harvest of squash and corn. This district was not lacking in large game to try the prowess of the Indian boy who was earning his first feather. The swift-footed deer and the wary doe, the strong shouldered bear and the wild cat, quick of muscle, constantly brought out the ctuhning in our child of nature. Nor was our dreamer shut in, as in a valley, so that his emotions for something beyond were stunted, for here we may find hills that overlook valleys and rivers and miles to more hills of rock and more tree topped ridges. These were the conditions under which our red men rove this part of our state. "One of the interesting spots in Wood County for an Indian village was at Skunk Hill on the old Meecham place. This Indian clearing covered about 20 acres and was an ideal location for the silent man of the forest. The north wind could not find the place, for behind it were high rocks and hills covered with dense woods. The south winds beat upon the village and with the warm sun the dreaming man was made more drowsy. The scenery from the Meecham place is one that promotes silent revery. Across the deep valley, six and ten miles away, the hills and clearings stand out vividly. The bluffs and hills of rocks, hidden by haze, to the distance of 35 miles could not but impress the old nature wonderer. Even to us, who are not imbued with the spirit of the great outdoors, this scenic panorama had a compelling, hypnotic influence.

"During the past summer a number of Indian families have lived on Skunk Hill near the camping grounds of their fore-fathers. These Indians were picturesquely living in their round bark houses and log huts. They all seemed to vie with one another in building and living the way their fore-fathers had lived. In the silent, somnolent forest they formed their round bark houses, as the Hebrew of old constructed the beautiful temple 'so that there was neither hammer nor ax nor any other tool of iron heard while it was in building.' A frame work of poles and branches was made and bound together. Then this frame work was entirely covered with large pieces of bark, firmly held in place by the tough, pliable, rope-like strips of dogwood bark. One of the brightest of the Indians, Frank Crow, said, 'Good house for summer the, but, ugh! bad, cold for winter.' Around the inner wall of this house is a platform 30 inches high and seven and eight feet wide. This is used for a lounging place by day and a bed by night. Their blankets were neatly folded up against the wall. In the center was an open place with dirty floor and a pile of ashes where they had cooked their meals on rainy days. On the bough rafters were hung roots of various kinds. They seemed to enjoy the quiet woods, and their language was still the language of nature life. As a rule they seemed to be clean Indians for they washed all the dishes after dinner, and swept the ground around the huts, and kept the place generally in order.

"We pointed at a new made grave and asked 'Who?' 'That was a young fellow, 19 years, died four weeks ago.' The grave was covered with cord wood sticks, and like the old Spartan burial it was placed near the house. 'Where does the spirit go after death?' Frank got very serious and said, 'All, both white man and Indian, go right to Great Spirit. The Indian and white man are divided. Indian goes that way (west) far, so far to the setting sun.' 'Then where?' 'Oh, we must not tell. Old folks tell us not to tell where Indian go. White man mustn't know.'

"The land question, the same problem that bothered the chief, King Philip, the orator Tecumseh, and Black Hawk, was constantly upon the lips of Frank Crow. We sat down in his bark house and rerfarked upon the beauty of the surrounding country. Frank broke in and said, 'Why don't you help us get our old lands? You white men should not have the whole country. The Indian once had this whole land. 3,236 years ago he first came in possession of it. But now what have we? We would like to stay here. This is a good place. White man want much for his land. White man wants all this land. The Great Spirit, the Great Chief up there owns all of this world, He holds this world in His arms as a father holds a baby. He meant us to have some of it. The first part of the century, the Great Father who lives way in the east, had a council down at Prairie du Chien, lots of Indians came to council, the lands were divided, and my tribe, the Menomonie, got all the land between the Wisconsin and the Black River, north to the place where the rivers nearly touch. (Probably near Medford). The Chippewas got land north of the Black. Fine no hunting ground. Much woods and streams. When granted this land, white man on this side of Wisconsin. Another man came. More came. We ask what are you doing here? I buy land of Great Father. Indian move west, soon no land for Indian. He poor, very poor!'

"The old Indian puffed on his pipe a long time and, in answer to a question regarding the history of his tribe he continued: 'When my grandfather was a very young man, he moved from the place where Chicago is, to where Milwaukee is. Then they moved to Hemlock Creek, west of Grand Rapids. When I was small, just large enough to shoot a partridge or any small bird, we moved to this place. About that time land was allotted on reservation in Shawano County. All must register. None of our band registered, so we must all stay on the outside of reservation. We soon moved back here. Then we were divided and some moved to county line (Saunder's place) and some south of Auburndale (Fred Graham's farm). This place here and south of Auburndale good for sugar camps. Skunk Hill especially good, south hill here, extra good.' These two long speeches were about all the old Indian could stand, and as he left us he pointed at his dinner of soup and unleavened bread which had been set out for him some time before. The village on the Saunder's place, which was in Wood and Marathon Counties, held nearly 400 Indians, summer and winter. The Indians are gone, but the springs which quenched their thirst on the Saunder's place are still flowing. And from their lands in Kansas the hills, rocks and stream-cut valleys are forever beckoning them to the lands which delighted their forefathers-to the silent forests of Wisconsin.

"The statement of the old Indian concerning the gathering at Prairie du Chien is corroborated in the Congressional record of the 57th Congress, in the volume on Indian treaties. August 19, 1825, the United States invited the Chippewa, Fox, Sac, Menomonie, Iowa, Sioux, Winnebago, and a portion of the Ottawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi tribes of Indians living upon the Illinois, to meet its commissioners, William Clark and Lewis Cass at Prairie du Chien. At this time the Menomonie claims were not settled as the boundary lines of the Menomonie were not definite. The chiefs with a number of Indians from each tribe constituted an immense assemblage of red men."

Grimm Mound Group. A group of five mounds is located on the Charles Grimm farm almost three-quarters of a mile east of Skunk Hill, in the northeast quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 32, Arpin Township, and across the road in the southeast quarter of the northwest quarter of the same section. One prominent mound in front of the house was excavated. It was four feet high and 30 feet in diameter. Three skeletons were found in it. The other mounds are all conical in shape, from 25to 30 feet in diameter and two to three feet high. The presence of this group of prehistoric earthworks as well as the discovery of a large cache of stone implements and other relics just west of the hill indicates that this hill was also a favorite spot for prehistoric Indians.

G. H. Reynolds and H. C. Fish in 1906 described a village site and cemetery on the old Meecham place at Skunk Hill, in the northwest quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 33, Arpin Township, as follows: "A trail ran westward from a village site at Skunk Hill in Section 33, Arpin Township (passing a village site in the west half of the southwest quarter of Section 31) to the Yellow River, in Richfield Township; thence northwest along the river to the north half of the northwest quarter of Section 28. Here it divided, one branch crossing the river to a village site in the southeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 30, the other running northeast for about a mile to Section 22, and thence northwest to a village site in the southwest quarter of Section 8."

There was a village and cemetery in Marshfield Township near the center of Section 3, and in Lincoln Township, in the northwest quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 24.

Marshfield Village Site.-In the northern part of Marshfield, near the City park, and on Central Avenue, near A Street, there was an Indian camp or village. Here they had a dancing-place and cemetery and wigwams covered with mats. There also was a camp where the Fourth Ward School now stands. As the white village grew in size the Indians moved farther and farther northward. Their last camp was on the bank of the creek north of the city. It is stated that at one time an Indian got drunk and handled his knife in too free a manner. A white man aroused at the Indian's behavior, struck him a blow on the head killing him (see Chapter on Marshfield). The next day the village was filled with hundreds of Indians. The white settlers were greatly alarmed that day.

In the early seventies there was an Indian scare in this section of the state. The Sioux came from Minnesota with scalps hanging to their belts and tried to stir the Chippewa to go on the warpath. They used all sorts of persuasion to accomplish this end. However, it was the boast of the Chippewa that he had never raised his gun against the whites, and all the fiery speeches of the Sioux came to naught.

The early settlers state that the Indians of that period were rather wild, but on the whole were good neighbors. There never was much trouble between the Indians and whites so long as the former did not obtain fire water. Some of these old white settlers say that the Indians were honest and were just as good neighbors to them as whites. Mr. Prosper Beauchaine, who first'visited the camp at the Grand Rapids in 1840, and who was one of the men who built the first camp in the Yellow River Valley in the winter of 1848-49, states that the Chippewa had many camps along the Yellow River known in Indian as Necedah River. Mr. Beauchaine settled in Lincoln Township in 1868 and was one of the first white settlers in this part of Wood County. He states that John Pottsveign settled at Bakerville in 1864. Mr. Pottsveign, also known as "Little John," married a Chippewa squaw. His home was at Bakerville just east of the present location of Lincoln Park. Mrs. Pottsveign had one brother, Aniwash, and another one, Peshen by name. The Chippewa bands made the Pottsveign place their rendezvous whenever they passed through this vicinity.

Other Indians well known along the Yellow River, and at the Pottsveign camp' were Rocky Run George and Good Hunter, both of whom served in the Civil War. Others were Black River George and Big Bull. Many Indians were buried on the Pottsveign place. John Pottsveign is also buried there.

The following interesting story appeared in the Marshfield News, in September, 1905:

"It happened 30 years ago -when all the white folks in and around Nasonville did not amount to as much as a good sized threshing crew. The Indians were plentiful then and for aught anybody knew were friendly to the- settlers. John Rausch, for it is he who relates the adventure, was a comparatively young man. He and his wife had chosen their home in the wilderness, built a house of logs and begun to clear what is now one of the best farms in that section. Near where the house stood was a spring of water, a fit camping ground for the red men. Mr. Rausch had but a few acres cleared which he had seeded to wheat. "One day in harvest time the chief of a small band came to him and asked permission to come on his land within easy reach of the spring. He gave his permission but cautioned them to leave things not belonging to them alone. Everything went smoothly until one afternoon when passing near this camp he noticed a number of children in the field filling their blankets with wheat which they shelled by rubbing in their hands. The shelled wheat they carried home and boiled like rice.

He drove them away but when he was gone they returned. The third time he caught them he was angered and in a threatening way said that if he caught them there again he would make soup of them, using the Indian expression for that dish. It had the desired effect for he never saw them there after that, but it was the threat he made that came near costing him his life.

"In the tribe was an old squaw that made baskets out of strips of wood. One day she went out in the woods to gather a supply of the timber from which to make the splints. She was accompanied by a little Indian boy seven or eight years of age. While busy preparing her bundle of sticks the little fellow strayed away and as he was nowhere to be seen when ready to return she came back to camp alone thinking he had returned without her. But he had not and his sudden disappearance caused a stir. This was on a Friday forenoon and a search was immediately instituted. Somehow from the beginning, no doubt from the threat he made they suspected Mr. Rausch. All that day and long into the night a vigilant hunt was kept up. The search was continued the next day, in which the settlers joined, but with no better success. Couriers were sent to different tribes then camping in that vicinity and with them came their two medicine men. The mother of the boy was frantic and believed in her untutored heart that Mr. Rausch had either murdered her boy or was holding him in captivity, and threats were made that unless the lost one was found his life would pay the penalty. It was their belief that the boy had been dragged to the spring and drowned, for on several occasions they were seen to search it closely, even poking into it with sticks. "In those times locks on doors were not so plentiful as now, the old fashioned latch taking their place. On the Sunday following the disappearance of the boy Mr. and Mrs. Rausch were treated to a most startling awakening. It was about five o'clock in the morning when both were sleeping soundly. They were suddenly aroused by the quilts being jerked from the bed and on looking up there stood the mother of the boy. She had quietly gained entrance to the house to determine if they held the child in captivity, and when she did not find him left as unceremoniously as she came.

"John had more hair on his head than he has now and to save it under these circumstances you can believe caused him some uneasiness. Sunday evening with no returns from the lost boy, a big meeting was held. A narrow tent with high poles and open at the top was constructed. On the top of the poles were bells. In the tent sat the medicine man and around were gathered the men and women of the tribe. Those on the outside beat drums and sang a dirge while the medicine man shook the poles and made the bells rattle. It was a queer spectacle but not without a purpose. The medicine man was to receive the great spirit who would tell to him the whereabouts of the missing one. John was about as much interested in the coming of the spirit as anyone and as it was an open meeting he sat on a log near by witnessing the scene which might decide his fate. As said before there were two medicine men. The first to go in the tent was one that had come from the Rice Lake district. The drums beat and the bells jingled but the spirit came not. Something was wrong, and appearing before the crowd the medicine man said it would be impossible to get the spirit until the pale face took a hike. Silently Mr. Rausch withdrew and soon the rattle and din broke forth anew. The spirit came and whispered in the red man's ear that the lost boy was dead. A scowl went over their faces, but not content with the decision, the other medicine man was asked to commune with the spirit. Again the rattle of drums and ringing of bells signified another communion. When quiet once more reigned and the medicine man came from the lodge and repeated the message the spirit had told him, a more happy look appeared on their faces-yet they were puzzled to know which message was true. With a wave of his hand he bade them be quiet and in measured tones said the boy lives. He knew it for the spirit had spoken to him plainly, even describing the spot which was in the deep woods far to the west. He was there sitting on a log crying. It was late at night when the council had finished, but before the break of day the next morning, the medicine man followed by a party of searchers started for the spot as directed by the spirit, and whether by circumstance or otherwise, the boy was found exactly as given out by the medicine man the night previous. He was nearly dead from exposure and hunger but when returned to camp there was great rejoicing. His recovery acquitted Mr. Rausch and it was hard to say which felt better over the return of the missing one, he or the Indian boy's mother."

Indian Hill Site.-There also was a large village on Indian Hill, west of the place formerly known as Hansen Station, Hansen Township. Mr. A. B. Cotey of Pittsville states that there were very many bark wigwams here.

The Winnebago.-The Winnebago of Wood County live on Hemlock creek in Seneca Township and for several miles along the road to Wisconsin Rapids. There are 127 adults and children in Wood County. and in the entire state they number 1284. They came to the Hemlock about the year 1910 and bought land from the white settlers. The Winnebago, have however, resided in the southwestern part of Wood County and on the Wisconsin and Yellow Rivers for a very long time. They still observe many of their tribal customs. Here they have small farms and gardens. In front of their frame houses they construct round or oval shaped tepees covered with canvas or mats of rushes. Here the women can be seen during summer making baskets or bead work, sewing, or cooking. Occasionally the bough frame of the medicine lodge remains standing, indicating where the dance was conducted. The Winnebago Medicine Lodge Dance is somewhat similar to the Potawatomi. These religion dances are conducted in the most solemn manner. The Medicine Dance and the War Bundle Sacrifice are their main religious functions. During the first part of August these Wood County Indians attend the annual pow-wow held in this county, when many scenes and customs are enacted for the benefit of the many white visitors. At the conclusion of this, almost the entire Indian population of Wood County resorts to the Wood County cranberry marshes, where they are employed during the cranberry-raking season. At some of the several large cranberry marshes in this county only Indians are employed raking cranberries. During the raking season, which lasts about two weeks, the Indians live in tents and wigwams at the marshes. After the day's work is completed the hours are spent at games, dances or other amusements. In the fall many go hunting, and in the winter they often hunt or trap, either at home, or else visit distant hunting grounds.

The War Bundle Sacrifice.-The war Bundle, of which there are a number of antique ones among the Indians of Wood County, originated through their legends at an early period. The original war bundle was given to an Indian by the thunder birds or Gods Above where the Indians carried this bundle in battle. It was supposed to protect them. It contained various charms and fetiches, such as little bows and arrows, war clubs, red paint, feathers, powders and medicines, as well as practical weapons, war clubs, bows and arrows, etc., these being saturated with the medicines in the bundle. The bundle also contained the skins of sacred birds of war, snake and weasel skins, reed whistles and deer-hoof rattles and buffalo tails. The contents of the war bundle vary according to instructions the owner received in dreams. The inner wrapper should be a white tanned deer skin, the external wrapper a reed mat or woven bag. The thunder birds commanded the Indian to respect the war bundle, keep it tied with a string and away from the women. To open it is a serious offense. It is only to be opened in time of peril and when sacrifices to it are made in the spring and fall, "when the thunderers are first heard." On the death of the owner the bundle goes to one of the owner's sons who displayed the most interest in it.

At the Winnebago ceremonies witnessed by the writer the British flag played an important part. The flag was a part of the bundle, or at least belonged to the original owner of the bundle, as well as the buffalo-horn head-dress worn at the accompanying dance. One of the flags that the writer saw at the ceremony floating above the dance lodge was an old British flag that Chief Winnishiek had received from the British at Prairie du Chien. The owners of this war bundle and flag are Frank Mike, and three other descendants of Chief Winnishiek. Frank Mike, being the most familiar with the ritual of the bundle has conducted the biannual ceremony for the last 30 years.

During the ceremony, the sacred fire having been kindled with bow and drill at day break and the flag raised, the bundle owner sits near the bundle, which is opened. The bows, arrows, and war clubs are stuck in the ground. The owner occasionally blows a reed whistle which he takes from the bundle, and amid the beating of the water drum and the shaking of the gourd rattles, speaks for hours praising the contents of the bundle. The guests or visitors sit about the lodge smoking their pipes and listening to the speech. The calumet is passed around by the attendant, holding the pipe in such a manner that the mouthpiece describes an arc so that the spirits might partake. Incense made of herbs is burned in honor of the thunder gods. Tobacco and occasionally flesh is given to the bundle and prayers are often offered for the cure of a sick person. Songs are chanted successively by members of various clans. The next part of the ceremony is the feast. A whole deer, bear, or other game, or else a dog, has been prepared and is eaten by the guests before the open bundle. After the feast was over the Buffalo Dance was given. Some one known to have special buffalo powers is designated by the host to lead off the dance. The latter puts on the buffalo-horn head-dress, which he takes from the buffalo bundle, which has also been exposed beside the war bundle, and commences dancing up and down the lodge. Soon all the men join in and follow the leader, imitating the running, pawing and bellowing of a buffalo. The squaws remain stationary at the east end of the tent, keeping time to the drum. After dancing around the tent for a time the leader gets down on all fours before a dish of maple water and drinks buffalo fashion without touching the bowl. The other dancers imitate him, and after all have partaken, the leader overturns the bowl with his horns.

Some Wood County Winnebago.-One of the best known Winnebago Indians in Wood County is George Monegar. He was born in 1868 northeast of Humbird, Wis. His father, Joseph Monegar, was born near Portage, Wis., and died in Nebraska at the age of 80. He served in the army during the Civil War in 1864; he volunteered from La Crosse and was a member of the Third Regiment, Wisconsin, Company F. With him in the same regiment were several other Indians from Wood County or to the north. They were Chippewa and Potawatomi. John Whitefish, Joe Wabena, and Be-ka-me all were in Sherman's army. George Monegar's grandfather on his mother's side, Carimon by name, visited Washington from near Portage in 1824, where he signed a treaty. He is buried on the bank of the Baraboo River where the city of Baraboo now stands. In the Chicago Historical Society museum is a picture of Carimon. George Monegar's ancestors came originally from Red Banks (according to George Monegar the Indian term for Red Banks was Mo ga sho ga ra) on the east shore of Green Bay. Monegar travelled considerably from 1887 to 1894 with Adam Forepaugh and also with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Shows. He also performed as a rider at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. Mr. Ed Wilson and Alex Lonetree are other well-known Indians from here.

In the winter of 1921-22 a Winnebago-Menominee half-breed woman from near the Hemlock died at the age of 99. Her name was "Pretty Hair." She was the oldest of the Wood County Indians. She is the first Indian to be buried in the Forest Hill cemetery at Wisconsin Rapids. She formerly lived at Keshena, Wis. When seen by the writer shortly before her death, she stated that her Indian name was Ai no lo mink and that she was born over a hundred years ago in the year when the stars fell. The writer procured a picture of the old lady. Another wellknown Indian who recently died on the Hemlock was Charles Wilson, father of Ed Wilson.

One mile north and one mile east of Babcock was a Winnebago settlement named after Chief Carimon, "Carimon's Settlement." George Monegar states that there are some mounds near Babcock. Other Winnebago camps and villages were at New Dam, Scranton, Van Tassel Point, and Squaw Creek. The village at New Dam on the east fork of the Black was one of the largest.

The Wisconsin River Mound Groups and Village Sites.-The southeastern portion of Wood County, the part traversed by the Wisconsin River, is very interesting, both from a historic as well as prehistoric standpoint. Groups of mounds are numerous along the entire course of the Wisconsin River. In Adams County there are over 600 mounds, and in Juneau County there are about the same number. In Portage County there formerly were a number of mound groups on the hills bordering the Wisconsin, some of which still exist.

The Chippewa, and probably also the Winnebago, had villages here. The Chippewa from up the river made periodical trips down the Wisconsin and had temporary camps here. The Menominee also visited Wood County occasionally. The two trading posts of Amable Grignon have already been referred to. They are both shown on a map of 1840. The first white settlement began in 1827, when Daniel Whitney from Green Bay obtained a permit from the Winnebago to make shingles on the Wisconsin River, and employed about 20 Stockbridge Indians, in addition to a white superintendent. (See Chapter VII on Early Settlement). Mr. Whitney's portrait may be seen in the State Historical Museum at Madison.

The southernmost group of mounds on the west bank of the Wisconsin River is situated in the southeast quarter of Section 21, about two miles south of Nekoosa, in Port Edwards Township. This was formerly a large and fine group. The northern portion of this group, which is still in existence, comprises about 17 mounds. There is one row or chain of about ten conical shaped mounds, the trend being east and west. The mounds are but a few feet apart, some being practically contiguous. They vary from 20 to 26 feet in diameter, and from 212 to 4 feet in height. It is likely that some of the mounds formerly composing this chain have already been destroyed. Those that are left are still in a good stage of preservation. Several hundred feet northwest of the chain is a long club-shaped linear mound, approximately 250 feet long. A similar distance southeast is another long clubshaped linear mound, with the following dimensions: present length, 248 feet; width, 8 to 22 feet; height, 2 to 2'2 feet. It tapers and points to the river. One end was cut off by the highway.

West of this linear is an oblong-shaped mound 90 feet long and 15 feet wide. The shape of the mound is not well defined.

South of the latter mound is a row of several oblong-shaped mounds. Several years ago these mounds were still covered with a dense growth of underbrush and some trees. These have all been cut away and very likely in another year or two the land will be plowed over and the remaining mounds destroyed. In the fields south of the mounds there still can be seen traces of former mounds. One of these partially destroyed mounds, situated at the southern extremity (northwest quarter of Section 28, Port Edwards Township) is still of large size and very conspicuous. At present it is of an oblong, oval shape and about four feet high. Some of the mounds of this group are described and illustrated in Volume XI, No. 2 of the Wisconsin Archeologist. They are mentioned as the Nekoosa group. Early settlers remember this part of the Wisconsin River bank as the location of an Indian village. Some of the Indians lived in frame houses and others in wigwams.

Mans Mounds and Village Site.-On the farm of Mr. Henry Mans, about a mile north of this group, and a short distance below Nekoosa, in Section 15, southeast quarter, Port Edwards Township, are several mounds. One large conical shaped mound stands in a cultivated field, about 400 feet from the river. It is 40 feet in diameter and at present four feet high, but originally must have been several feet higher, as much material was removed from it. Mr. Henry Mans formerly owned a collection of relics found on this land. They are at present in the collection owned by Mr. Clark Lyons of Wisconsin Rapids.

In the woods, on the southeast quarter of Section 15, on the same farm, and on the west side of the highway, are still one or several other mounds. In these woods and across the highway on the river bank was one of the largest and best known villages of the historic Indians in this part of Wood County. Until quite recently the location of the bark houses and eight or nine cabins located here, as well as the gardens, could be distinguished. The occupants most likely were a mixed band, at one time composed of several hundred Indians. , There was a large cemetery in the woods already referred to.

When the first white settlers came into this region, these Indians were almost entirely of pure Indian stock. Later on many half-breeds from near Green Bay settled here. Mr. M. Marcoux, an old settler here, states that these were French and Oneida, or Stockbridge, half-bloods.

The original Indians appear to have been mostly Chippewa, and probably some Winnebago. One of the old chiefs went by the name of Oshkosh, probably meaning Osh-ka-ba-wis. Mr. Hiram Calkins, a former resident of Wausau, states (Vol. I, 123 W. H. C.) that in 1854 "The Wisconsin River Band of Chippewa numbers about 200 Indians and occupies the country from Grand Rapids up to Tomahawk Lake. The head chief of this band is Osh-ka-ba-wis, or The Messenger; the head brave is Ka-kac-o-na-yosh, or The Sparrowhawk; the chief orator is Now-o-com-ick, or The Center of the Earth; and the chief medicine man or conjuror is Mah-ca-da-o-gung-a, or The Black Nail, who performed the feat of descending the Long Falls in his canoe, and is represented by the other Indians as being a great medicine man. He is always called upon from far and near in cases of sickness, etc."

There were also some Menominee in Wood County. However, the Menominee are not mentioned by early settlers much on the west side of Wisconsin, except those who belonged to the Potawatomi bands. Wood County was primarily Chippewa, and to a lesser degree Winnebago territory. The Indians of this particular village left soon after the white settlers arrived for their respective reservations. Some went to Lac du Flambeau, others to Shawano. The half-breeds occupied this village for a considerable length of time thereafter. Of these Peter Lawndry or Landreigh is mentioned as one of the chiefs. Mr. Marcoux at one time asked one of these Indians the question who constructed these mounds in this vicinity. He replied that they were constructed by the "Black Hawk" Indians who had lived here many years previous. An old Indian at Hatfield to whom the writer put this same question answered that they were built by an extinct tribe whom he termed Ma-say-ha-nee.