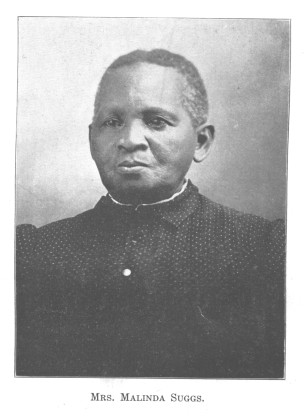

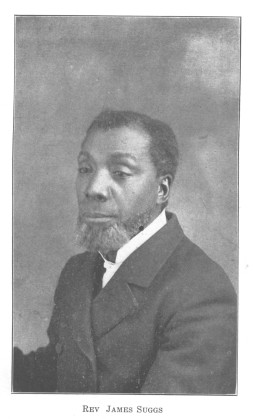

My father and mother were slaves. Father was born in North Carolina, August 15th, 1831. He was a twin, and was sold away from his parents and twin brother, Harry, at the age of three years. This separation, at so tender an age, was for all time, as never again did he see his loved ones. In after years he had a faint recollection of his mother, and could remember distinctly the words of introduction with which he was handed over from his old master to his new: "Whip that boy and make him mind." A slave had no real name of his own, but was called by the name of his master; and whenever he was sold and changed masters, his name was changed to that of the new master. The parents gave his first, or Christian name, however, which was usually retained amid all his changing of masters. Father's parents named him James. So at this time his name was James Martin. He was sold by Mr. Martin for a hundred dollars, and taken to Mississippi. Afterward he was sold to Jack Kindrick, and again to Mr. Suggs, with whom he remained until the war broke out. Father was a blacksmith by trade, and was considered a valuable slave. Mr. Suggs was a kind master, and as James was an industrious and obedient servant, he was allowed the privilege, after his day's work was done, of working after night for himself. He made pancake griddles, shovels, tongs, and other small articles, the proceeds from the sale of which brought in many a small coin. He was also allowed, in odd moments, to cultivate a small garden patch, on his own responsibility, and it was surprising what that little patch was made to yield. Naturally proud and ambitious, the money thus obtained was usually spent upon his person, enabling him to dress better and appear to much better advantage than his less enterprising compeers. Slaves were not allowed to have an education. Father said he had to "pick up" what education he got, much as a rabbit might be supposed to pick up some tender morsel with the greyhounds hot in pursuit. When the master's children came from school, they would make letters and say, "Jim, you can't make that." But he would make it and find out what it was. Again he would say to them, "You can't spell "horse, "or "dog," or some other word he wanted to know. And they would reply, "Yes, I can," and would spell it. All this time he was learning, while they had no idea that he was storing these things up in his mind. Yes, he had to steal what learning he got. While James was still quite young, Mr. Suggs bought a little slave girl, named Malinda Filbrick. In time, Jame and Malinda came to love each other, and were married while yet in their teens. The same pride of heart which had manifested itself in his own stylish appearance, now prompted him to lavish his extra earnings on his young bride. One instance of his extravagant indulgence was the purchase of a $7.00 pair of ear-drops, which doubtless afforded him much gratification until the ill-fated day when they proved too strong a temptation to a party of Union soldiers, who carried them off as spoils. Another outlay of his surplus earnings was in the purchase, for his wife, of a remarkable quilt, made after the pattern known as "the chariot-wheel." This was truly a masterpiece of skill, and was highly prized by my mother. It seemed about to share the same fate as the ear-drops and was in the hands of a Union soldier, when the earnest pleadings of my mother prevailed upon the kind-hearted officer in charge to give orders for its restoration.

While still in slavery, father was wonderfully converted. Before his conversion he was a wicked young man. Pride in dress was not his only besetment. He loved to danc and drink, and have as good a time, from a worldly standpoint, as any human being could who was held in bondage. Whenever a slave wanted to go out to spend the evening he had to get a pass from his master; for there were more men called patrolment, elected according to law, whose duty it was to seize and thoroughly chastise any slave who was so presumptious as to venture out without a pass. If a slave was caught out after nine o'clock at night, without a pass, he was stripped to the waist and beaten thirty lashes on his naked back. It was against the law to whip a slave over his clothing. One night these patrolment caught father out without a pass. He well knew what was to follow, and as they held him by the coat collar, he straightened back his arms and ran out of the coat leaving it in their hands. They got the coat, but James never got the whipping. After he was converted, he would go to his master and ask to be allowed to go to meeting, and permission having been given, he would say, "And please, sir, may I have a pass?" At these meetings he would talk and exhort his fellow-slaves, until Mr. Suggs would say, "If James keeps on like this, he will surely make a preacher." Father loved freedom; or at least he thought he should enjoy it. He never had been a free man, and hardly knew how it would seem to be free. But it is natural to every man, of whatever race or color, to want to be free. He used often to say to his young wife, "When the car of freedom comes along, I am going to get on board;" meaning that if he got a chance he was going to the war. One day the news came that the "Yankees" were within four miles of Ripley, the village near which Mr. Suggs lived. They were reported as having a heavy force of both calvary and infantry. Mr. Suggs was a very wealthy man and had a large number of fine horses and carriages, as well as great herds of cattle and sheep. All these he must hide, as best he could, from the "Yankees," for they were very destructive to the property of the southerners. So he called his men to gather up his belongings, as far as possible, and take them to the cane-brake to hide them. The canes grow so thickly together, and the leaves so interwoven, as to make it impossible to see any object at a distance of even a few feet. So a cane-brake was a fine place for hiding. Mr. Suggs called James and told him to take his sheep and go at once to the cane-brake, which he did. Little did my mother think, as she saw him go, that this would be the last she would see of James for three years and nine months. But so it was to be. When the "Yankees" came, a colored man took them and showed them where these treasures were hidden, together with the belongings of several neighbors. The soldiers helped themselves to whatever they wanted; and told the slaves that any who wanted to do so might go with them. Father thought his time had come to strike for liberty. He went into the war and fought for his freedom and that of his family, and obtained it as a well-earned victory. Many of the slaves, in making their escape north with the Union army, took with them their wives and children. So father fondly hoped he could get some soldiers to come back with him to get mother and the four children. He knew but little of army life and discipline, and so was bitterly disappointed in never getting back. When the excitement was over and the soldiers gone, and some of the slaves came back to the plantation, father did not appear. Mr. Suggs came to mother and said," Malinda, where is James?" "I don't know," said mother. "Didn't you send him off with the sheep?" But he would not believe her when she said she didn't know. He blamed her for father's going away, and thought she had put him up to go. Father enlisted in 1864, but was wounded shortly after and discharged from active service and sent to the hospital. After recovering from his wound, he joined the regular service and continued until the close of the war, part of the time acting as corporal of his company. When the war was over, he came north with his captain, Mr. Newton. The thought uppermost in his mind, was how to get his family from the south. For him to have gone after them, in person, at that time, would have been at the risk of his life. Mr. Newton, having business in the south, and being a kind-hearted man, father begged of him to go and find his family and bring them to him. This Captain Newton did, finding them not far from where father had left them. Father now went to work with great zeal at his trade to earn money for the purpose of getting a home for his family. He was at last a free man, with his dear family -- a freefree country. The slaves could not be married as white people were; for there was a clause in the marriage ceremony which gave the slave-holder the right to separate husband and wife whenever he chose to do so. I have heard my mother say that she has known instances where husband and wife have been separated after having been married only a few weeks, or even only a few days. My father said that seeing he was now a free man, he wanted to be married like other free people. So on the fifth day of June, in 1866, father and mother were married again according to the Christian rites, or according to the white man's law. Father continued to work at his trade until God called him to preach the Gospel. He had a great struggle over his call to preach. He had worldly ambitions and was making money, and it was hard for him to give up all and follow Christ. Finally he consented to preach, but did not go at it with his whole heart. He would preach occasionally, but still worked at his blacksmithing, until one night the Lord spoke to him plainly. He said it was like an audible voice saying, "Either preach the Gospel or work at your trade." He was to niake his choice, but it meant to him heaven or hell. Which would he take? He trembled as he felt the responsibility of leading lost souls to Christ. But he made his choice and said, "Yes," to God. He began preaching around in school houses. Large crowds gathered to hear him, and from that time on, it was the business of his life to minister Divine truth to dying men and women. In 1874 he was given exhorter's license, by Rev. C. E. Harroun, Jr., in the Illinois Conference of the Free Methodist church. In 1878 he was given a local preacher's license by Rev. Edwin C. Best, pastor of the Sheffield circuit, Galva district, of the Illinois Conference. In 1879 he was ordained deacon in the Illinois Conference, by General Superintendent B. T. Roberts, and in 1884, in the West Kansas Conference, he was ordained elder by General Superintendent E. P. Hart His labors during the early years of his ministry were in the Illinois Conference. Rev. C. W. Sherman came to Princeton, where we lived, with a band of workers and held a tent meeting. This band consisted of C. L. Lamberts and wife, F. D. Brooke, and Lizzie Bardell, now his wife; D. M. Smashey, and Belle Christie, now his wife. These band workers have since developed into prominent preachers and evangelists in the Free Methodist church, some of them having filled the office of district elder for several years. They were at this time entertained in our home. While the meeting was in progress one night the rowdies gathered, cut down the large tabernacle and threw stones into the small tents. Brother Sherman tried to persuade them to desist when one struck him in the eye, nearly putting out his eye. Brother Smashey received a cut in his head, from which pools of blood stood around the tent. Next morning my father looked down toward the camp ground and saw that the tent was down, and he and mother went down with sorrowful hearts to comfort the workers. Brother Sherman met them with a joyful, "Praise the Lord, Sister Suggs, I shall preach tonight if I haven't either eye." And he did, with a bandage around his eye. And with another bandage around Brother Smashey's head, they looked like soldiers after a battle. The Lord gave a grand victory, for the hearts of the people were turned toward them in sympathy. A good collection was taken to defray the expenses of the meeting; the tent was raised, and the meeting went on with power. Souls were saved and added to the small society already organized in that place. The city authorities promised protection from future disturbance, and kept their promise. In the year 1879 father went to Kansas as an evangelist. This was the year of the great drouth and grasshopper scourge. There was a colony of colored people, who had come from the south and settled in Graham county, Kansas, naming their little settlement Nicodemus. Father went to preach to these people. He found them in a suffering condition, nearly starving, and with scarcely enough clothing to cover their nakedness. Father visited Hon. John P. St. John, at that time Governor of Kansas, to see what could be done for these people. The governor sent him back to Illinois to solicit aid for them; for, said he, "After you have provided for their temporal needs, then they can hear your Gospel." He solicited accordingly in Illinois, and sent back barrel after barrel of clothing to the people, He afterward took up a homestead in Phillips county, Kansas, and in the year 1885 brought his family to Kansas. He was now almost constantly in the work of the Lord. He often said, "I would sooner wear out than rust out," and surely God granted him the desire of his heart. But while he was thus working earnestly to build up God's kingdom, Satan was just as busily at work to hinder and destroy his labors. Jesus said to Simon Peter, "Simon, Simon, behold satan hath desired to have you, that he may sift you as wheat; but I have prayed for thee." Ah! here was Peter's only strength, "I have prayed for thee." In the power of those prayers, and in that alone, could he overcome. The same old enemy is in the world today and his hatred and spite toward God's children is just as strong as it was in Peter's day. He still desires to have God's little ones that he may sift them as wheat. The powers of darkness were now turned loose upon father. Wicked men laid hands upon him and took him to prison. This occurred on the camp ground at Marvin, Kansas. One afternoon, after he was through preaching, some one came up to him and said, "Brother Suggs, some one wants to see you." He was led out supposing he was going to have a talk with some old friend or with some one who was inquiring the way to God, as many such came to him for counsel. He found himself being handcuffed and being hurried away between two disguised detectives who accused him of being one Harrison Page, an escaped murderer. In vain he pleaded innocence. "You are Harrison Page," said his accusers. "Your name is not James Suggs. You are a murderer." Imagine his surprise! But the Lord blessed him right there, and as he was led away, he was heard praising the Lord. 'The last word he said to the brethren was' "Take good care of old Dollie, and see that she has plenty of water, take her home, and tell wife I will come out all right." One looking on observed, "Any man in such a condition as that, arrested and accused of murder, taking thought of an old horse like Dolly, surely can't be a very bad man, Suggs is innocent." Rev. C. M. Damon was tireless in his efforts for father's release, and with characteristic foresight, telegraphed a friend in Topeka to see the Governor, and wrote to ex-Governor John P. St. John and to father's old neighbors in Princeton, Illinois. Rev. E. E. Miller, now in heaven, pursued after the captors, the brethren made up money to pay his expenses and kept him right after them, until father was proven innocent and set free. Doubtless it was the intention and expectation of the enemy, in making this bold accusation, to silence father forever from preaching. But in this he overshot the mark. Father never ceased preaching on this account; but on the other hand, it gave him new opportunities for preaching the Gospel. Even in jail he held meetings, and one man who heard him was converted and called to preach. Father lived convictions on his accusers. He talked to them about their souls and their hard hearts melted. They knew he was innocent, and really wanted to get rid of him before they could do so. His accusers were afterward arrested and brought to trial. After father was cleared and released, and while waiting for his accusers' trial, he started a meeting in Osborne, Kansas. Thus God caused the wrath of man to praise him, and opened new and unexpected doors for the spread of the Gospel. This arrest and seizure of father, and the suspense which followed, were a strange and hard ordeal for the family at home. My mother has been through the fire, but the same God who was with her in slavery days was with her at this time. Father was mercifully restored to his family, all safe and sound, and went on his way rejoicing. Doors of usefulness were opened to him on every side. He was quite widely known within the bounds of several different conferences, the Illinois, Iowa, West Iowa, Kansas, West Kansas, and Nebraska conferences, each having claimed some share of his time and labor. Attracted by the Free Methodist Seminary at Orleans, Nebraska, and desiring for his daughters the advantages it afforded, he moved his family thither in 1886. But he did not settle down or superannuate because he had moved to a community that was well supplied with preachers and Christian workers. It was only for convenience and the welfare of his family that he was led to take this utep, and not with any intention of dropping out of the Lord's work. From this as a center, he went out to different places for evangelistic labors, and kept the revival fire burning brightly in his own heart through the heat of summer as well as through the cold of winter.

The last winter he was on earth, being the winter of 1888-89, he was engaged in a protracted campaign against sin, on the Sappa Creek, in Norton County, Kansas. He pitched his tabernacle on the farm of "Father Neimyer," and here once more set the battle in array. He banked up the tabernacle on the outside, and put in it two stoves, which made it very comfortable. The attendance and interest were good, and souls were born into the kingdom of God. After closing this series of meetings in the tabernacle, he held others in the neighboring schoolhouses, and thus put in the winter solidly for God. It was the privilege of my mother and myself to be with him in all these meetings. How little we realized that these were his last on earth! He returned home from his winter's campaign, weary and exhausted. He decided to rest a little and be ready to go again. After resting a few weeks he went on an evangelistic tour east, but soon returned home again sick, and took his bed. His disease baffled all the skill of the physicians, and after an illness of about five weeks during which he manifested great patience and resignation, on the 22nd of May, 1889, he passed peacefully home to God. His funeral at Orleans was largely attended, not only by his brethren and sisters in the church, but by the citizens of Orleans who thus showed their appreciation and respect. But none knew his worth so well as his own family. He was the strong staff upon which mother and all of us had leaned. How should we ever learn to walk alone? "Leaning on the Everlasting Arms," we have since learned to mount up on wings as eagles over all our difficulties, to run the Christian race and not grow weary, and to walk with the Lord and not faint. Father, we miss thee -- as much now as ever we did -- yet would not recall thee. Rest, weary soldier, rest from thy labors! Thy works shall follow thee. Thy reward shall be sure. A part, at least of your family is travelling the road our father trod. We have caught the spirit of your loved battle song, and sing with you,

By and by God shall say to each one of us, as he said to you, "It is enough; come up higher."

And then, when the last battle has been fought, and the last victory has been won, and the last enemy has been destroyed, then and not till then, shall we lay our armor down, and through all eternity, "We will walk through the streets of the city |