|

"When we are sick, where can we turn for succor? My mother was born in Alabama, April 5th, 1834, and when quite young went with her parents to Mississippi. Her mother was a slave belonging to a Mr McArthur. He had several sons and when he died his slaves were divided among his sons. In the division, parents and children were separated from each other, and thus mother was separated froin her mother and eight brothers, but not far. She could go and see them occasionally. My mother was never ill-treated like some of the slaves were, but my poor grandmother was. One night while the old man, McArthur, was still living, he and one of his sons went to town. They were both in the habit of drinking. So on this particular night they got drunk and gambled away their money and came home in a rage. Grandmother had to sit up late to keep their supper warm. She was afraid to go to bed, but finally dropped to sleep and the fire died down. Sometime in the small hours of the night, they came home. With a start she awoke, and tried to fix the fire. But as she stooped to stir the fire in the fireplace, the old man kicked her in the eye and put it out. But this was not punishment enough. Early the next morning he called her out to be whipped. What was all this for? What was all this for? What had she done? He accused her of stealing his money! So she was stripped to the waist and beaten on her naked back until it was raw like beef, and as he threw the whips with which he had beaten her on the ground, the dogs licked the blood from them. But grandmother must continue to go to the field and work, notwithstanding her raw back and consequent high fever. My mother was a little girl then, and while grandmother was being beaten and was crying so, the little girl would scream and pretend to be sick, thinking the master would surely let her mother go to come to her sick child. But no! He paid no attention to her screams. After the old man McArthur died, my mother was taken by one of the sons. But he being a hard drinker, got into debt and my mother had to be sold. A Mr. Fillbrick now bought her. Mrs. Fillbrick was a good Christian woman, and took a great deal of interest in her little slave girl. She taught her to read and was always kind to her. She would sometimes talk out her heart to mother, young as she was, perhaps for want of any one else to talk to. At such times she would tell her that it was very wrong to keep slaves; but as she was not strong enough to do her own work, and had to have help, of course it was necessary for her to buy one. Mother was the only serin her house and necessarily had much work to do. Mrs. Fillbrick, although so kind and gentle in disposition, was not very well liked among her neighbors and mother often wondered why. But after she was older she knew the reason. It was because Mrs. Fillbrick opposed slavery. Speaking almost prophetically, she would sometimes tell mother that some day the slaves would all be free. Soon this woman left the south, and of course, had to sell her slave. Mr. Suggs, my father's master, now bought her, and thus my father and mother were brought together for the first time. After they were married they were never torn from each other and sold to different masters; for Mr. Suggs said he did not believe in separating husband and wife. Thus God dealt very tenderly with my parents and spared them the horrors and heartaches which were the common lot of most slaves. Under this comparatively kind and indulgent master, my mother knew little of real trouble. Her first experiences that might be called real troubles came after my father had gone to the war. Mr. Suggs, fearing that my father would come back and get mother and her four children, took the two older children, Ellen and Franklin, to Georgia. I will say here; that when the Union soldiers were around the slaves could just walk off before their master's eyes, and he dare not say a word. So by separating the family, Mr. Suggs seemed more likely to prevent their escape with the Union soldiers. When Ellen and Frank were sent away, Lucinda, the next little girl, would have been taken too, but she was sick at the time. So she and baby Calvin were left with their mother. And now followed dark days for mother. Husband gone, she knew not where, and herself blamed for his escape; and now her two children in strange hands and carried away to a strange land! She had also a sister belonging to the same master. To add to her troubles, her sister died at this time. It seemed her cup of bitterness was more than full. Baby Calvin was very cross. Mother had no time to care for hiin properly, as she was the only woman servant on the place and had ten cows to milk and all the cooking to do. So her little children were neglected, for this work must be done. One day Calvin was sitting on the kitchen floor crying loudly, and mother had no time to take him. The mistress came in, and hearing the baby crying, she chugged his head up against the brick wall. How he did scream! Mother said, "You had better kill him and be done with it." The mistress angrily replied, "Let the nasty stinking little rascal behave himself, then; he is a chip off from the old block," meaning he was too much like his father. Mother was professing religion before father went away, but was ignorant of the way of real salvation; and instead of her troubles driving her nearer the Lord, she wandered further and further away, and at last ceased praying altogether. Her troubles preyed upon her mind so that she lost her appetite and could. not sleep. She grew weaker and weaker until she could no longer get through with her work. Finaliy she came to herself. She thought, "I must not die, but must live for the sake of my two little ones. She began calling on the Lord for help, wept her way back to the cross, and was restored to the Divine favor. There came to her new strength and courage to meet life's battles. She inquired of the Lord as to whether she should ever again see her husband and children. Clearly and definitely came the answer, "You shall see them again." She began trusting in the Lord, and was touched and helped in her body. As to any direct word from her husband, she had none. He wrote her letters but they were destroyed. Many a false report concerning him was conjured up and poured into her ears by her unfeeling mistress, who would come into the kitchen, light her pipe and sit leisurely down to rehearse to my mother what she had heard about "James," every word of it the product of her own fertile imagination, and told purely for the purpose of making mother miserable. So when the mistress appeared at the door of the hut, and lighting her pipe, sat down for one of her cheerful (?) interviews, mother usually knew that some big story was to follow. She would preface her remarks by saying, "Well, I heard from James today. The 'Yankees' have got him." And then would follow some horrible recital of how the "Yankees" had him chained to an anvil block and were starving him to death, or something else equally consoling. At such times mother would calmly answer, "Oh, well, he is as well off there as he would be here." The slave-holders who had sent their slaves to Georgia to prevent the "Yankees" getting them now began to think that the war was about over, as everything seemed to calm down; and Mr. Suggs said with the others, "Well, we can bring our niggers back now, the d--d Yankees have left Corinth." The general feeling was that of safety, and there was little fear that the Union army would again bother them. So the exiled slaves were sent for, and with them came mother's children, Ellen and Frank. They had been abused and sadly neglected, but in answer to prayer, they were restored to their mother. But the calm in which they had trusted was the calm of death. It was the lull before the bursting of the thunderbolt. The "Yankees" returned in greater numbers than ever, and in less than two months peace was proclaimed. Mother could see so clearly the hand of God in the restoration of her children in His own appointed time and manner; as had they been left in Georgia until the close of the war, it is very doubtful, humanly speaking, as to whether she would ever have seen them again. And for this reason: So long as the slaves were considered property, each owner naturally looked after his own belongings and kept them together. After the slaves were freed, however, no one cared what became of them. And so it was at the close of the war, that many families were separated and were never reunited. My mother had eight brothers and sisters, and cannot tell where one of them is today. That she ever got back her children was due to God's own arrangement and overruling. But this curse of African slavery is done away. Thank God! Parents and children, husbands and wives, are no longer torn from each other and sold as cattle to enrich their master. We have one Master, even God. We have lived to see the day when "all men are born free and equal," and this despite of race or color. The blot of African slavery has been wiped out from our fair land with the life-blood of her brave sons. But there still exists, in our very midst, another, and even, more cruel slavery, which is holding men soul and body in the most abject bondage. It is the slavery of Intemperance. The white man's slave could love and serve the Lord and in the end get to heaven. The Drink Demon's slave is held with an ever tightening grip in life, and is ruined, body and soul, in death. Shall we see the curse of strong drink wiped out even as we have seen the curse of slavery? Shall we have an Emancipation Proclamation for the defenceless millions over whom drink is now tyranizing? I appeal to you who are voters. Shall we? After mother was set free, she left her old master and went to work out. Ellen and Frank were old enough to do a little; so they were put out to service too. One day there came a letter to mother. In it was a lock of father's hair. She knew the hair and the handwriting, and knew it was no fraud. This letter told her to prepare to come north with Captain Newton. Could it be possible that so much of good was in store for her? Yes, it was really true. Mr. Newton had gone to Georgia and would be back again in a month after her and the children. But he being a Union man, it was dangerous for him to stay long in the south. So he had to hurry back and come for mother sooner than he expected. But she left all and went with him, and the long-divided family were now at last happily reunited.

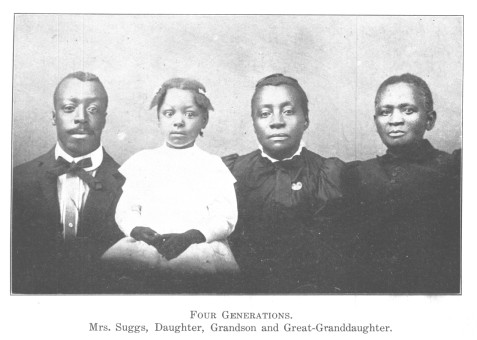

Of these four children born in slavery, Ellen is the only one now surviving, Lucinda died with typhoid fever at the age of eight. Calvin took quick consumption from exposure in Michigan, and died at the age of nineteen. Franklin grew to manhood and was married. Three months after his marriage, he was drowned in a lake near Elgin, Illinois. Ellen, the eldest child, now Mrs. Ellen Thompson, lived in Elgin until two years ago, since which time she has lived near Omaha, Nebraska. After the days of slavery, while my parents were living in Bureau county, Illinois, there were born to them four daughters, Sarah Matilda, Katharine Isabel, Lenora Ethridge, and the writer, Eliza Gertrude, all of whom are still living. During my father's last illness he often spoke to mother about temporal needs, and would always end by saying, "The Lord will provide." And truly He has. Mother in her declining years has a comfortable home, free from debt, near the church, where she delights to attend. She is always found in her place in the house of God unless prevented by illness. And although getting along in years, she is seldom ill. She gets a pension and with this gets along nicely. Verily, the willing and obedient shall eat the good of the land.

|